Joëlle Dubois is Painting the Weird, Messy Beauty of Bodies

Words: Chris Erik Thomas.

Bodies are strange. They fold and scrunch and twist. They grow hair in odd places and, over time, morph into all shapes and sizes. They are the things we’re all living inside and yet, only a sliver of the diversity of bodies that exist are elevated and celebrated in popular culture. That’s an error that the Belgian artist Joëlle Dubois is attempting to correct.

Born in Ghent in 1990, Dubois was raised in a culture that had yet to break out of the narrow mold of acceptable bodies. “The women around me always seemed to be unhappy with their physique, always trying to obtain a standard that’s not attainable. As a woman, I also incorporated that behavior,” she recalls. It has been through her art that she has reclaimed the narrative around what is acceptable — and accepted her own body. Take even the most cursory glance at the artist’s oeuvre and it’s clear that Dubois has a passionate love for the diversity of people. Her paintings are fun, mysterious, and extremely online. In nearly every piece, a cell phone is in the hand of her subjects. Some take selfies while others lounge in bed scrolling endlessly, either alone or with a partner equally transfixed by the soft glow of their screen.

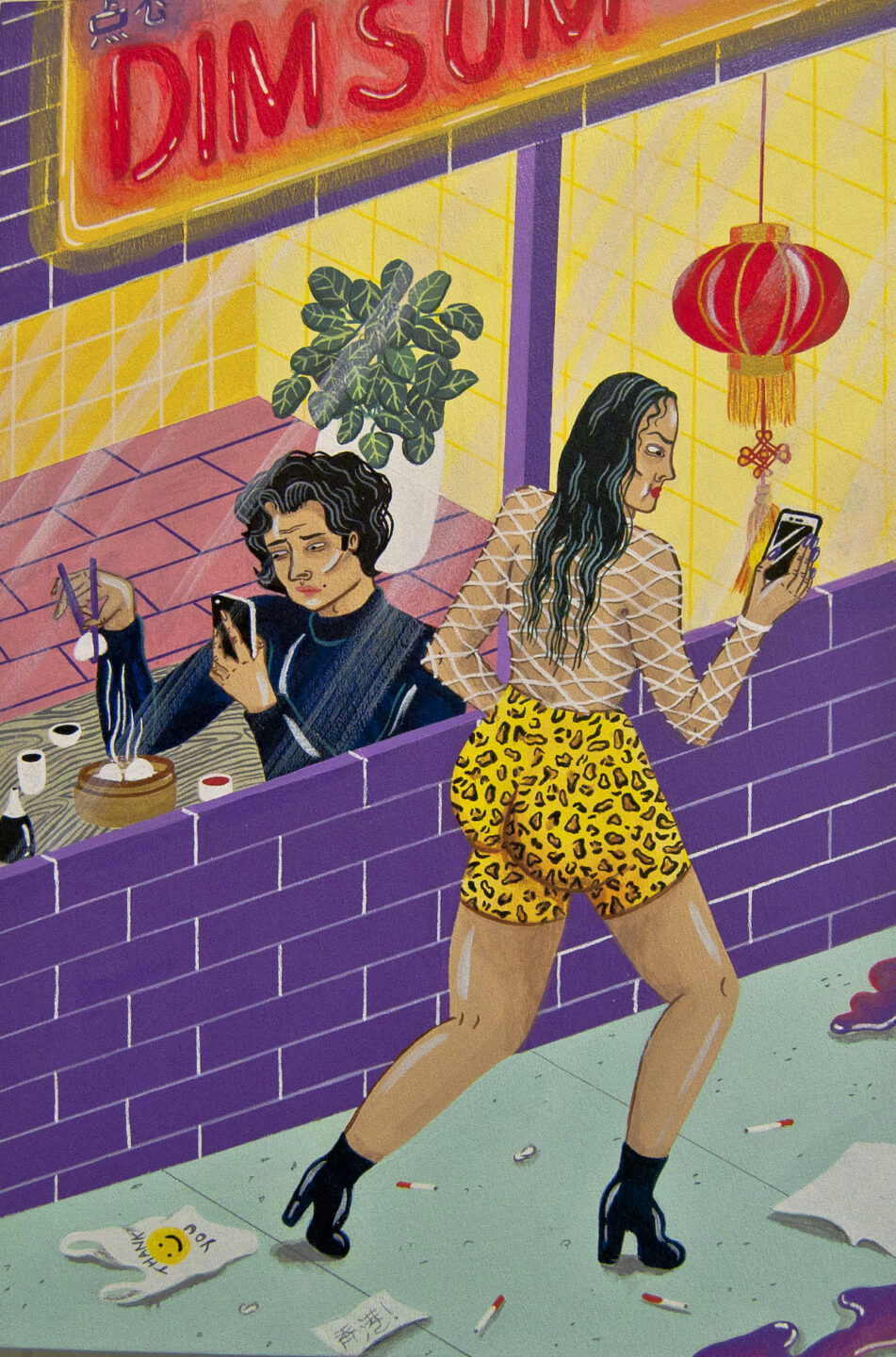

After making her debut in the contemporary art scene in 2015 with a handful of shows in Brussels and Gent, the artist’s unforgettable paintings have won her recognition far beyond her home country. It’s easy to see why. In an art scene still so heavily dominated by stale works crafted under the leer of the male gaze, the unapologetic reclamation of nudity as something vulnerable, not sexual, gives each piece she paints a sense of kinetic energy. Her scenes of messy rooms, nude selfies, and dim sum dinners spent glued to a screen are relatable.

Ahead of her inclusion in Thomas Rehbein Gallery’s booth during this year’s edition of Art Düsseldorf, we talked to Dubois about the unrivaled artistic stimulation of art fairs, finding inspiration on Instagram, and more.

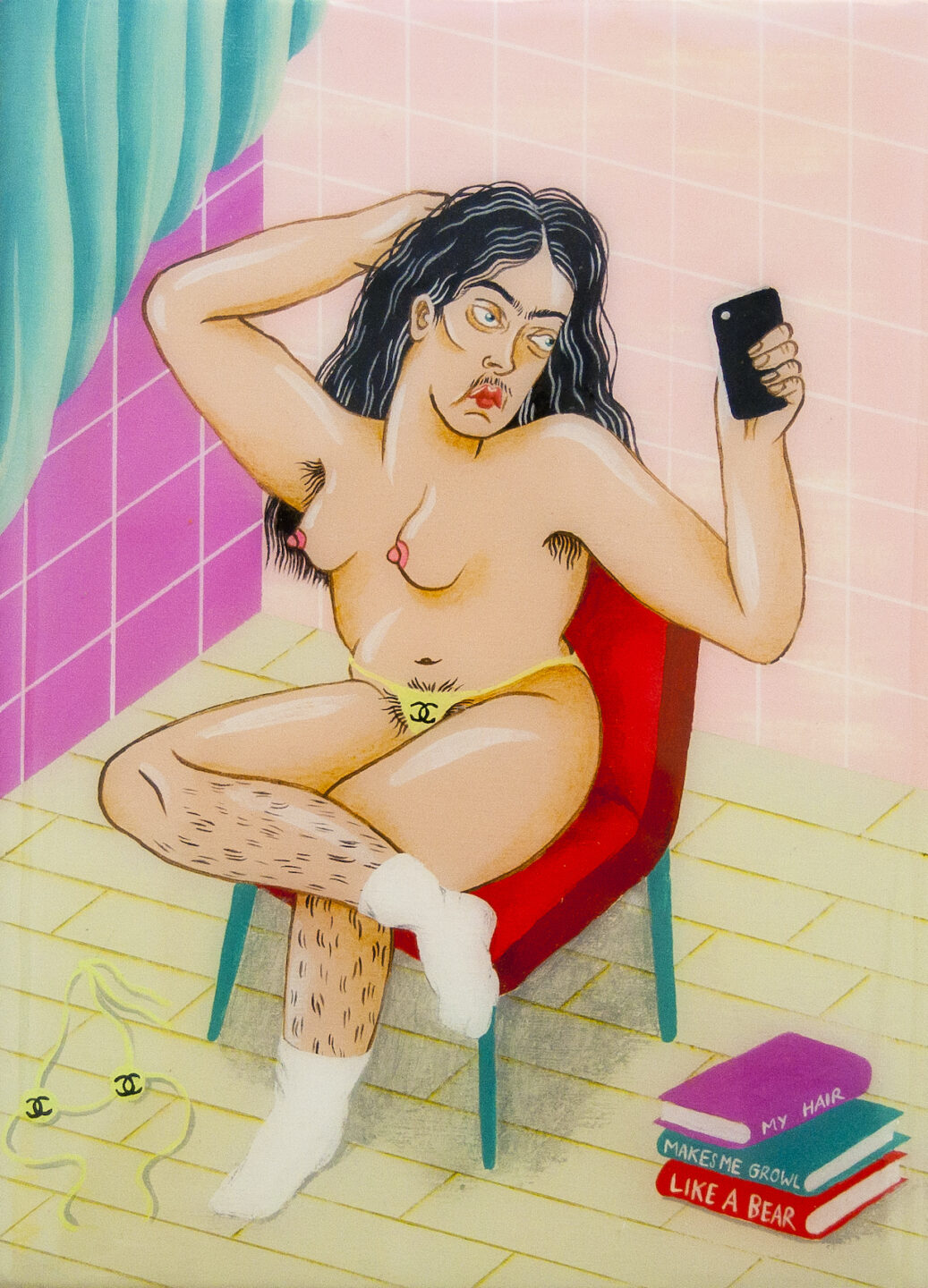

Joëlle Dubois. "Dawn", 2019. Acrylic on wood. 116 x 89 cm. Courtesy Thomas Rehbein Galerie.

Joëlle Dubois. "Dusk", 2020. Acrylic on wood. 116 x 89 cm. Courtesy Thomas Rehbein Galerie.

You came of age at the start of social media. What has been your personal experience navigating social media? What are the positive aspects of social media for you?

People unabashedly spread their intimacy over digital media. Everything revolves around the cult of the body. I am fascinated with this behavior so it’s quite simple: social media is an infinite source of inspiration. Online I often find an idea for a piece. There can be an overall theme in mind but I don’t quite have the composition yet. So whenever I feel really stuck, I’ll let myself sit and go through Instagram to try and spark something.

Online I can see a particular person, scene, or even just a color palette and I’ll be like, “Okay, that’s the inspiration. This is what I want to use and reference.” I often take a screenshot and at the time of the piece’s creation, I try to combine an event that’s happening in my life with this imagery. Then I also refer to different masterworks within classical art that I think contain the theme that I’m looking to communicate.

Aside from my work, I believe that social media can connect people more easily. I know a lot of people that have met through Tinder and after a few years, are still happily together – like myself actually. I think that lifestyle kind of reflects in the work I make.

What message do you want viewers to take away from the art you’re showing at Art Düsseldorf?

I reflect on the daily absurdity of life and try to capture “weird” and “messy” human experiences. So I guess the art pieces I made are representations of life and the varying emotions that accompany it. Meanwhile, leaving ample space for the viewers to interpret and enjoy the stories I portray.

Joëlle Dubois. "Bodyhair Don't Care", 2019. Acrylic, epoxy on wood. 23 x 17 cm. Courtesy Thomas Rehbein Galerie.

The people I portray have more to offer than their sex appeal.

Joëlle Dubois. "Say Cheese", 2017. Acrylic, epoxy on wood. 20 x 15 cm. Courtesy Thomas Rehbein Galerie.

What inspired the works you have on view at Art Dusseldorf?

I think about surrealism a lot and I want to try new things out, like adding unexpected things to a certain scenery. Also, the characters that are portrayed by Fernando Botero and his depiction of the female form intrigue me.

Social media is inextricably tied to nudity and, more specifically, the policing of bodies. Your work often features nude or semi-nude people. What statement or message do you hope is conveyed to viewers through your work, especially on this issue?

There’s so much erotic and nude imagery within the fine art. And I think that’s where the influence came in. But also as a critique, in a sense, of what’s considered decent or indecent. I try to normalize the natural body and depict body positivity. In our culture, there was certainly a lack of it for years. I remember when I grew up, the women around me always seemed to be unhappy with their physique, always trying to obtain a standard that’s not attainable.

As a woman, I also incorporated that behavior. So in a way, it’s an attempt to accept [my] own body in a way. Now there are a lot of plus-size models and I see a lot of women who are embracing their curves and body hair. I think it’s beautiful and it shouldn’t be censored. The people I portray have more to offer than their sex appeal. That’s how the cone boobs came to be, for example. I make my individuals more chunky and try to paint people that are not necessarily traditionally beautiful because I don’t want to sustain the image of that blank ideal of beauty. So nudity is in the first instance something vulnerable and human and not something sexual.

How did you get involved with Thomas Rehbein Galerie?

We met during one of my first art shows in Brussels in 2016. Thomas saw my work there and gave me further opportunities from that. In 2018 I got my first group show with them in Cologne. That then led to our future collaboration, we clicked right away.

Joëlle Dubois. "Liking Tongues", 2018. Acrylic on wooden panel. 21 x 15 cm. Courtesy Thomas Rehbein Galerie.

How important are art fairs for you as an artist? Has that changed at all because of the pandemic?

Art fairs are fun because for me it’s a way to get stimulated. It’s an opportunity to connect with art lovers, galleries, or to get introduced to new artists. After visiting an art fair I’m always energized and ready to start working again. I think the pandemic challenged galleries and artists to find new, creative ways to display and sell art, but I believe there is nothing more satisfying than looking at a painting in the flesh and not on a screen. I think we are all ready and excited that events like this are happening again and for me, it increased the urge to exhibit.

Technology like VR and AR and “the metaverse” look like the next big thing in social media. Would you like to explore these technologies with your art, or do you prefer more physical mediums like painting and drawing?

Honestly, I’m pretty terrible at anything technological so it’s quite obvious why I prefer a physical medium. Painting can be equal parts therapeutic, fun, challenging, immersive, and frustrating — and it changes regularly as you work on a piece. Because we live in such a digital age, we sometimes forget how important nature actually is. That is why I like to contrast new-media related topics with this traditional way of creating.

While painting, I escape my ego and get in touch with universal time because there is no time and space. I am completely in the now and there is nothing better than being in this flow. It is an attempt to arrive at the right frequency, the frequency of nature around me. That’s why I never remember how to do anything. Every time I paint a phone, for example, it feels like it’s a new experience. I’m like, “What? How did I do this last time?” It’s kind of ridiculous. But I also like to challenge myself, so I am recently exploring installation art and maybe I’ll incorporate mediums like video in the future.

You’ve been called “voyeuristic” in many statements about your work. It’s a word that has been used to describe many artists throughout history, including the likes of Andy Warhol. How do you feel about that word and do you see yourself as a voyeur or something more complicated?

The first thing you learn at art school is to look, to gaze, to stare during life nude drawing classes, for example. As a visual artist, you are a constant observer of things which you appropriate for creative pursuits. So the artist’s gaze is fundamental in the search for subject matter and for me, technology offers a new way of seeing and being seen. So yes, I guess I see myself as some kind of voyeur. But the creative process is not necessarily a voyeuristic experience, if voyeurism is defined as gaining sexual pleasure from watching others.

Joëlle Dubois. "She Makes It Work", 2021,. Acrylic, epoxy on wood. 30 x 25 cm. Courtesy Thomas Rehbein Galerie.

Joëlle Dubois. "Dim Sum in Hong Kong", 2019. Acrylic, epoxy on wood. 30 x 20 cm. Courtesy Thomas Rehbein Galerie.

How has your artistic practice adapted to the pandemic?

It has been hard to stay inspired and focused when society has been thrown into chaos. I was constantly switching from feeling down and being tired to reminding myself of the importance of creating and the joy it brings me. I think a lot of my work is experiential and a lot of elements come from life experiences. So now there’s some darkness, stillness, and sadness in my recent work that comes from this pandemic experience. There’s also a desire to tell a story or be able to relate to people and tell stories that I think everyone goes through.

Your subjects are often in compromising positions and have a range of body types and sizes. How have the subjects of your work changed over time? Especially in terms of diversity?

I’m not sure that I consciously think about how my influences or subjects change over time. Or how to blend all these sources into something that is mine. I just paint what I like, how I want to paint it. Of course, the early work still looks related to the work I do now, but it’s becoming much simpler in certain ways. In terms of diversity, the [early] figures were captured in a very distinct and sexual way. Active participants in their own world with their own complex stories.

The figures now are more pronounced and curvier, still sexual, yet they are not here for your viewing pleasure. They are absent of the male gaze. You can stare at them and they will never recognize it. If they are sexual, their sexuality is entirely detached from the needs of the viewer, and so power is stripped from the viewer and accumulates within the image itself. That power is granted to those who identify with the image: women of all body types, ethnicities, and identities. Therefore the male gaze is transmuted. So these subjects can be considered empowering.

Chris Erik Thomas is the Digital Editor of Art Düsseldorf. They work as a freelance writer and editor in Berlin and focus primarily on culture, art, and media. Their work can also be seen in Highsnobiety, The Face Magazine, and other publications.