Samira Elagoz is a Radical, Silver Lion-Winning Art Provocateur

Words: Chris Erik Thomas.

There’s no introduction or hand-holding in the work of Finnish-Egyptian artist Samira Elagoz. Watching one of Elagoz’s films requires trust because the journey will be gripping, experimental, and, for some, uncomfortable. That’s the point.

The art he makes isn’t made to be easily digestible. It’s made to help Elagoz explore his own identity. During the early period of his career — from 2013 through 2019 — Elagoz identified as a female artist and created films documenting his exploration of gender. In 2014’s “Four Kings”, he sent out a simple ad on Craigslist seeking strangers to form a connection with on camera. “The concept is that I meet you at your place and film how we get to know each other,” his ad reads. The resulting film won acclaim and landed Elagoz a Blooom Award at that year’s Art.Fair Cologne. A follow-up theatrical work, “Cock, Cock… Who’s There”, tackled themes of rape, female bodies, online dating, feminism and the male gaze — leading the artist on a five-year tour around the world that garnered many awards for the work.

Eight years (and multiple equally-experimental works) later, Elagoz began 2022 with another award — the prestigious Silver Lion at the Venice Biennale Teatro — for entire body of work, including his most recent film, “Seek Bromance”. The sprawling, 220-minute film is a time capsule of his relationship with Brazilian artist Cade Moga during the pandemic, from the first meeting to the final breakup. “I consider that perhaps this could be the theme of our collaboration,” his initial email to Moga reads. “The relationship between 3 lovers, the camera being one of them.” As the work progressed, it became as much an ode to connection as it was a farewell to Elagoz’s femme identity.

It’s a gripping narrative journey that signals Elagoz as an important, rising force in the experimental art world. During a break from his busy schedule of touring “Seek Bromance”, we caught up with Elagoz about navigating the art world as a transmasculine artist and why the internet is key to creating his works.

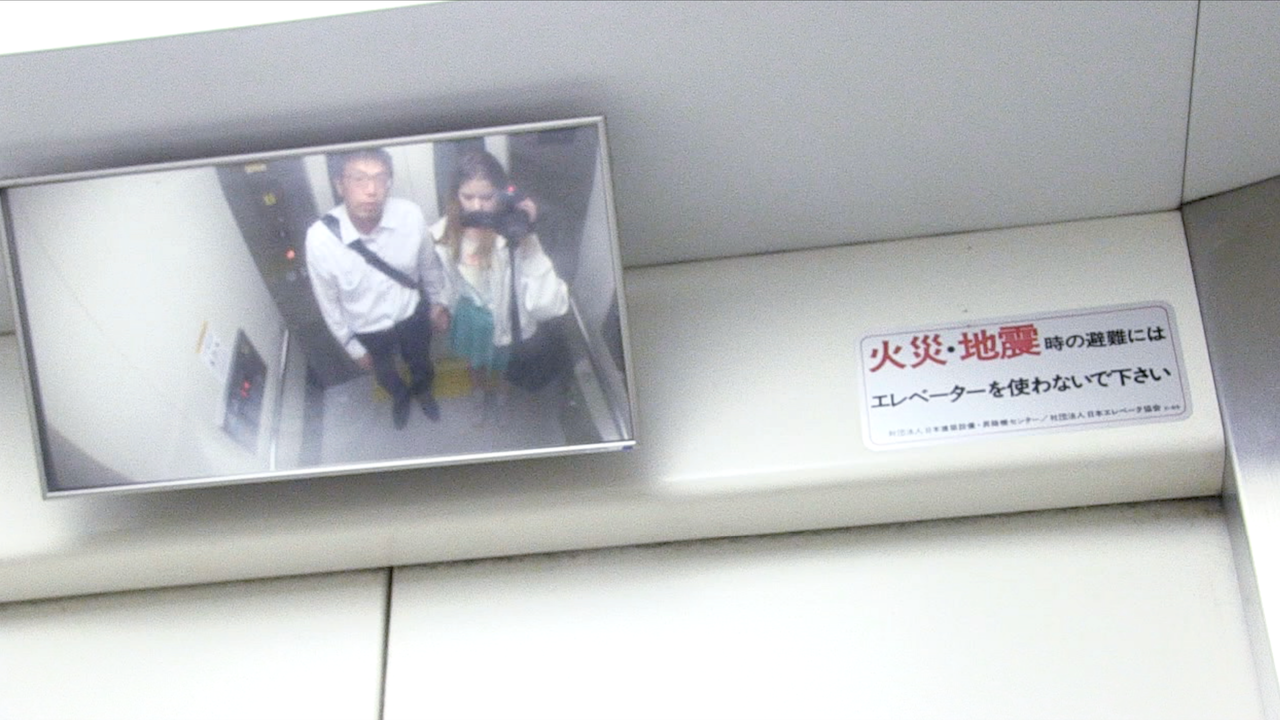

Samira Elagoz. "Seek Bromance", 2021. Courtesy of Samira Elagoz.

Samira Elagoz. "Seek Bromance", 2021. Courtesy of Samira Elagoz.

For many artists, the pandemic allowed them to slow down and evaluate their artistic practice. For you, it led to a piece of art that was both professionally and personally transformative. What reflections have you gathered about that period?

Covid was a pretty devastating hit to most artists, while also [being] a collective burnout where everyone had to slow down. I had to cancel plenty of my projects; my plans to collaborate with several artists across the globe were squashed. My last project, “Seek Bromance”, took on a completely different form once I arrived in LA to film one of my collaborators on the exact week Covid hit. We met at the start of the lockdown, and spent the next few months together, filming and waiting around. I did not want to make a Covid work, but the backdrop of that is, of course, unavoidable. The effects it had on our interaction, on my transitioning, the cabin fever, have all shaped the work considerably. That’s why I call “Seek Bromance” a romance situated at the end of the world.

You grew up in the Finnish village of Karkkila. What was your introduction to the world of art? How did it evolve over your adolescence?

I’m a ’90s kid and spent half my youth in a dilapidated house in the middle of the forest brought up by a poor single mom. We didn’t have a car and there was pretty much nothing to do, which left a screaming desire to get out and taste the world — experience something giant and real. The only escape there was watching movies. My first touch [with] art making was dancing. Now, looking back, I think the only reason for such an endeavour was that that tool was free; my body was available at all times. But films were the art form I appreciated the most, and I’m happy that I eventually did end up working with film.

You have been quite strict about not using actors or scripts and not working in studios. Why are these restrictions important to you and your artistic practice?

The moment I started working with the camera changed everything. Coming from a technical dance background and having a lot of experience in watching “talented performers”, I got bored with it and the idea that I would train people to be as I’d like them to be. I’d much rather pick people and allow them to be as they are and capture that and my relation to them. So I made the conscious choice not to be an artist that works in a studio with colleagues, but rather, make work that is unrehearsed and co-starring people I have never met before. In all my work, life has to happen first, and then I make something out of it. That’s why I work without a script; there is unpredictability. I always set out to gather up real-life events.

Samira Elagoz. "Craigslist Allstars", 2016. Courtesy of Samira Elagoz.

Much of the art world is ruled by a narrow scope that favours the cisgender, white, male archetype. What has your experience been like in navigating the industry first as a high femme-presenting and now transmasculine artist?

While it has been exciting and meaningful to get to show work, I’m not going to lie. It has often been frustrating and saddening. Throughout my whole career, I’ve faced a lot of simplification and [been] stripped of complexity. Most of my works also speak on topics that are not spoken of[ muhc], such as the effects of rape on your sexuality or transmasculinity. That sets up a whole bunch of pressure on you as you become a sort of voice for your community, which is something no artist should be expected to do.

One should not and even cannot represent the whole “community”. While I have been thanked for being a “rebel and progressive”, the more pertinent question is: who are the rebels and progressives among the establishment? Who are the radical curators, festival directors, and funding decision-makers? Without those people recognising the merit or need of a rebel artist, you don’t really do anything with the radicality of the artist.

Continuing on from the previous question, what positive and hopeful experiences have you had as an artist within the art world?

My works talk about topics like sexual violence, gender roles, and transition, so I often get to see how behind people are with their thinking. The most positive experiences have been when I sensed that I evoked a change in the audience. My last work was about sexual trauma, so for me, it’s most touching when other victims said it empowered them. With “Seek Bromance”, I’ve heard so often it was “life-changing” not only for trans but cis people. Hearing comments like that is one of the best rewards you can have as an artist.

A lot of your oeuvre is focused on researching men through the lens of intimacy and masculinity. What are some of the most impactful insights you’ve gathered from this research?

I always try to construct my work in a way that I won’t give ready-made answers. I want the mic to turn towards the audience in the end. They should be left with a desire to articulate what they think about these things. From what I’ve heard, this happens more often than not. I spent 10 years of my life filming men on and off, and there is a soft place in my heart for them. Hopeful and amused. I have often felt like a confidant to men. Cis men are usually bad examples of masculinity; they’ll appear a bit hopeless and unwilling to progress at times. As a transmasculine, I feel the burden is on me to be better while their crisis awaits its revolution.

Samira Elagoz. "The Young and the Willing", 2018. Courtesy of Samira Elagoz.

Samira Elagoz. "The Young and the Willing", 2018. Courtesy of Samira Elagoz.

The internet, particularly online advertisements, has formed the basis for many of your works. Before the start of your art career, what was your early experience with the internet and online ads? How has this experience evolved as you’ve incorporated it into your art?

All my works start online. I have found most of the people I’ve filmed through online platforms. Or often, they have found me. I’ve always been a digital romanticist; I think online platforms give you a chance to redefine yourself. And there is an instinct to be less private with online strangers and more honest. I used to be an extremely socially anxious person and also lived in the middle of the forest, so [being] online was everything. I started chatting immediately as a kid when we got our first home computer 20 years ago. I think that sexuality and romanticism online are as real as they can be [in real life]. In fact, I believe that online, we get to connect in a more honest way, or at least honest to ourselves.

You’ve spoken about the “multiple realities” that are present in before-and-after images of trans people. Can you speak more on this idea of multiple realities, especially in regard to art and gender?

In a patriarchy where women, trans, and marginalised people have not had the right to be large, contradictory, blurry, and abstract, but are rather pigeonholed, stereotyped, and simplified, art became the place to explore. A place where you can be expansive. I felt that by showing my “former versions” with my “current version”, I could make real the fact I exist in multitudes and encourage the exploration of multiple selves. The construction of a self, creative or otherwise, is complex, and claiming multiple selves pushes back against the flattened reading of othered bodies.

Looking towards the future, what themes or ideas are you hoping to explore or are actively involved in exploring?

I will continue with the concept of strangers. For almost ten years I’ve been researching gender dynamics, visiting men’s houses with my camera, investigating the female and queer gaze and touring the world with [four] works about them, so I’d also want to write a memoir eventually. I find it endlessly fascinating to work without a script and with people I’ve never met before. The thrill I get from not knowing what I will film, who I will film, and what the dynamic will be, keeps me going.

Chris Erik Thomas is the Digital Editor of Art Düsseldorf. They work as a freelance writer and editor in Berlin and focus primarily on culture, art, and media. Their work can also be seen in Highsnobiety, The Face Magazine, and other publications.