Anna Ehrenstein’s Art Collabs Are Fusing the Global South and West

Words: Chris Erik Thomas.

Two things are immediately clear about Anna Ehrenstein: she is incredibly brilliant and incredibly busy. Once described by a critic as a hybrid of “petit bourgeois” and “hoodrat”, the artist has spent years showcasing her ability to blend so-called “high” and “low” culture through a mix of video, installation, sculpture, writing and other mediums.

In the years before she began to produce her challenging, highly aesthetic art, Ehrenstein grew up experiencing firsthand the kinds of sociopolitical power imbalances that impacted her parents. “Who has the power to live and who has to die through a visa system is something that was super central [for me], but was something that took me a while to understand,” she explained on a recent video chat. As she bounced between German and Albanian society, the concepts of geopolitics began to take root — eventually making their way into her artistic practice.

Her work has allowed her to teach viewers about the kinds of experiences and issues that molded her own upbringing, while also helping her to collaborate with fellow creatives around the world. She has worked with everyone from the Columbian voguing group House of Tupamaras (“Tupamaras Technophallus”, 2020) to the Senegalese fashion collective DONKAFELE (“Tools for Conviviality”, 2018) — the latter of which won her the C / O Berlin Talent Award in 2020. More recently, she teamed with 4DHD on “Coffee Ground Imaginaries” (2022) as part of the Screen City Biennal, which was one of eight exhibitions that opened this past September. For Ehrenstein, the work is all part of her overarching goal to “use beauty and awe to make great projects, speak truth to power, and have fun with friends.”

As the Office Impart- and KOW-represented artist took a short break to breathe between her many ongoing projects, we sat down for a video call with Ehrenstein to talk about her new exhibitions, balancing research with art-making, and why collaboration is key to her artistic practice.

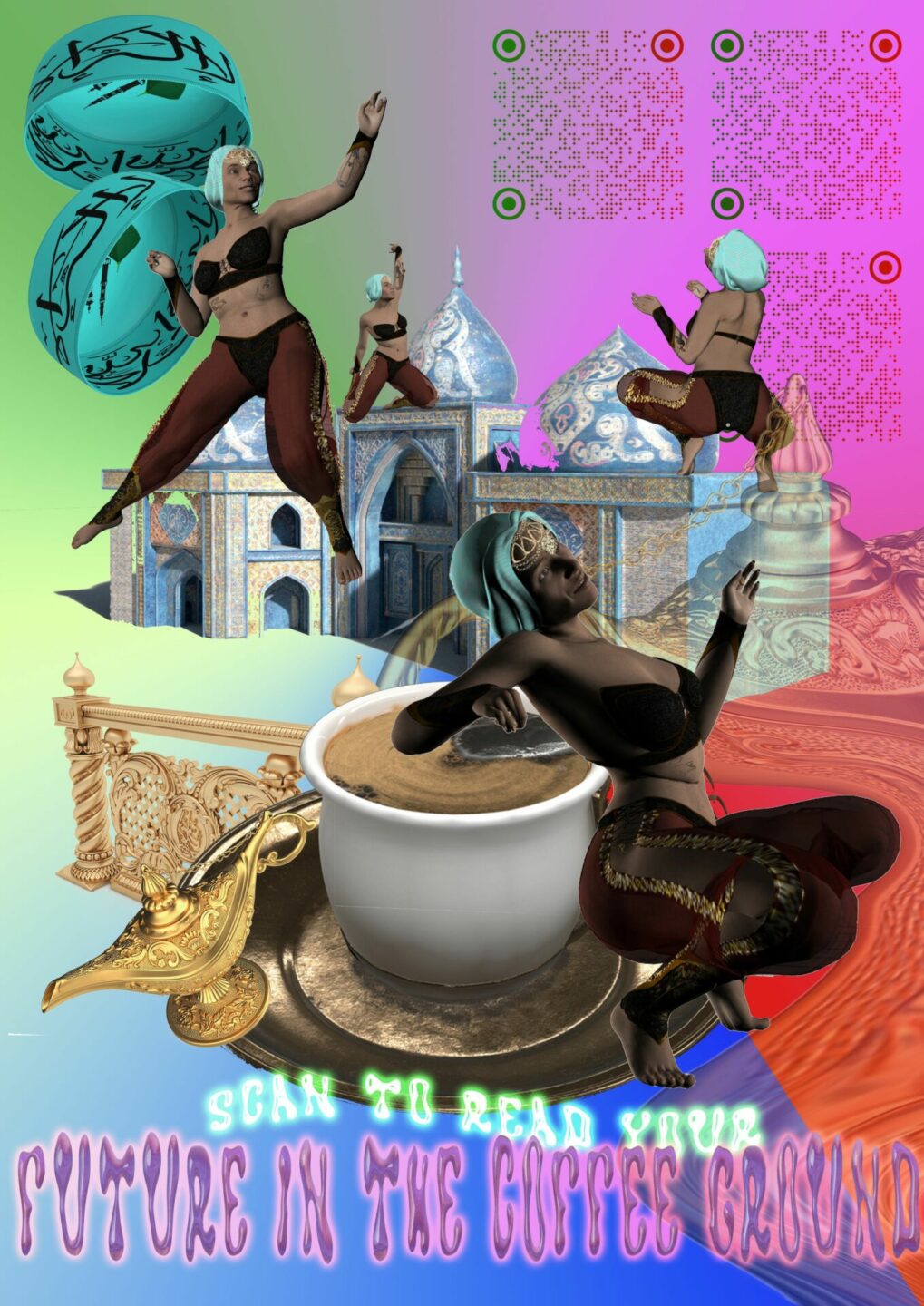

Anna Ehrenstein and 4DHD. "Coffee Ground Imaginaries", 2022. Courtesy of the artist.

With the Screen City Biennale exhibition, what is the focus of the work?

The Screen City Biennial asked me for a commission and I told them that I had this piece that I would like to continue developing. I did a performance work [in 2019] that was called “Coffee Ground Imaginaries”. Usually, in my culture or a lot of Middle Eastern cultures, there’s this tradition of reading an individual’s future in the coffee grounds; my mom sits down with her friends on Fridays and looks for their future. Since a couple of years, we are in a continuous crisis, so I thought one could use this methodology to also look for collective futures. [We made] six AR filters spread in a stroll through Berlin and then through Oslo afterward.

Many artists are afraid to work with new technology like AR. For you, it’s a natural next step.

It’s been super fun because I’ve also been doing 360 video works for a couple of years, but my education really comes more from a 2D than a 3D space. When I was painting in 3D for the first time, I had a feeling like people who were in the cinema a hundred years ago — like, “Oh my God, I’m seeing something that brings the future.” I’m a little tech geek so I love playing with technology, but the thing that sometimes keeps me from using certain new technologies is that there is a fetishization of like, “Okay, we’re going to do NFTs now and it doesn’t matter what the fuck and why we are using this medium.” It’s just hyping technological progress. It’s also tied to very heteropatriarchal ideas of progress and of fetishizing the new without actually trying to put things into a bigger social context.

Anna Ehrenstein and 4DHD. "Coffee Ground Imaginaries", 2022. Installation view at Archenhold Observatory. Courtesy of the artist and Screen City Biennial.

Anna Ehrenstein and 4DHD. "Coffee Ground Imaginaries", 2022. Installation view at Colonial Village Karpfenteich in Treptower Park. Courtesy of the artist and Screen City Biennial.

Collaboration is a big part of your artistic practice. When you first started creating art, did you start with collaboration or has that aspect worked its way into your practice?

No, that definitely has worked its way in. I studied photography by coincidence. I just wanted to do something with art and my mom was like, “You’re only allowed to move out if you have a place to study.” I came in with an idea that I want to do something creative and stumbled upon documentary photography. That had my inner social justice warrior completely excited and then I actually realized what a neocolonial tool journalism actually is. I was quite shocked about the power imbalances within photography. I started looking more at curatorial methodologies and all of these things came together. I was like, “Okay, if I want to continue working with photography, I have to break this binary of me looking at people.”

Collaboration is such a big trend in the art world and quite often people are like, “Oh, I collaborated with someone,” and then this other person has no agency. There are always power imbalances with collaboration. In every human interaction, there are power imbalances, but it gave me a chance to try to disrupt the colonial legacy of photography and the power imbalance inherent in gazing at somebody.

How do you find the people to collaborate with? Or does it just come naturally in your research?

It’s always a hybrid. Every project is different. For example, with House of Tupamaras, I applied to do a residency in Colombia with a completely different research focus, and then friends of mine were like, “Yo bitch, you’ve been part of a queer scene in Berlin for a while. You’re going to Bogota. There’s some friends that have other friends.” You see their work and you’re just like, “Oh my God, I just want to work with you.” It was a completely natural project. [It can be] really difficult because I do not come from a lot of privilege, but I’ve inherited a lot of privilege by now. Sometimes I am the only person in the Global North that can represent a bigger collective of people that work in the Global South, but it’s usually always worth the battles.

Anna Ehrenstein. "Tupamaras Technophallus", 2020. Video still. Courtesy of the artist, Office Impart and KOW Berlin.

Anna Ehrenstein. "Tupamaras Technophallus", 2020. Video still. Courtesy of the artist, Office Impart and KOW Berlin.

How much of your artistic practice is research versus creation?

Research plays a big part. It’s probably 50/50. I’m waiting for the point when administration is going to become zero and I won’t have to take care of that shit; nobody told me before becoming an artist that administration is bigger than anything else. It will be really hard for me to ever leave the art world [because] it’s the only place where you can do emotional and associative research combined with scientific research to create something pseudoscientific that makes sense for yourself.

For example, the show that [opened] with Office Impart in September, [“The Balkanization Of The Cloud”, 2022], looks at the nation-state through Instagram influencers and how digital propaganda and the deep states have changed our political landscape. For the work, I [collaborated] with two great artists: Lux Venérea, who’s a Brazilian performance artist based in Berlin, and Jonathan Omer Mizrahi, who is an Israeli filmmaker and also a performance artist. Lux has been looking at [Jair] Bolsonaro’s distribution of fake news in the Brazilian context, and Jonathan has been looking at greenwashing and agriculture as a settler colonial practice in the occupied West Bank and Palestinian lands.

I [got an] education in hypnosis for the second part to hypnotize the internet. I have a diploma now as a hypnosis educator. This was the first time I was doing an actual education for something. Everybody else [in the course] was a therapist or psychosomatic doctor, and I was like, “I’m an artist and I want to hypnotize the internet for a video work.” That’s a fucking intense privilege to be able to create works that work like this. Academia wouldn’t give it to you. Filmmaking alone wouldn’t give it to you. But the art world gives this space to create these types of synergies.

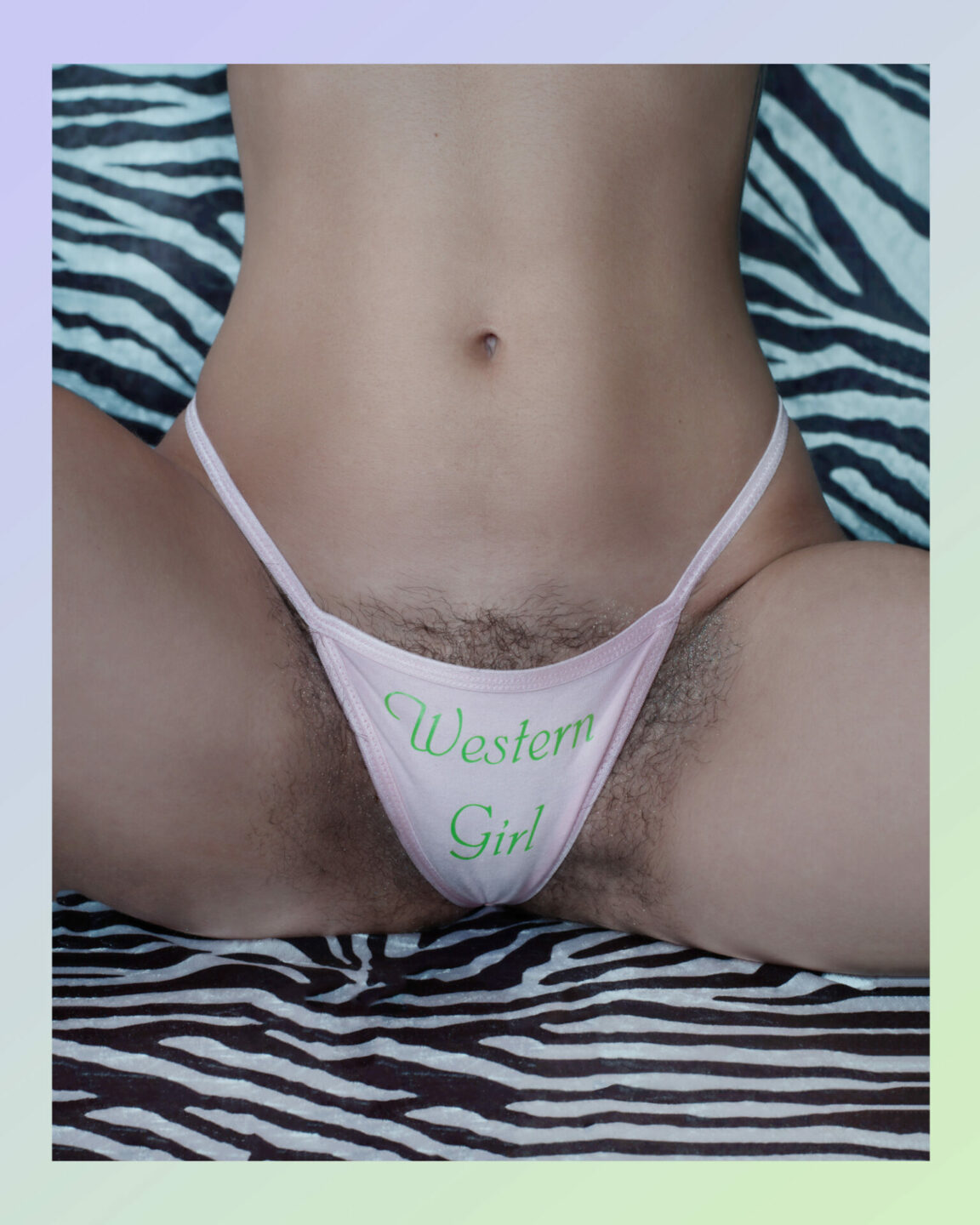

Anna Ehrenstein. "Western Girl", 2017. From "Tales of Lipstick and Virtue", 2013–2018. Courtesy of the artist, Office Impart, and KOW Berlin.

Anna Ehrenstein. "Abdourrhamane", 2021. Courtesy of the artist, Office Impart, and KOW Berlin.

You are so incredibly busy. Do you ever get overwhelmed?

I’m definitely a workaholic but I just love my practice and I love the encounters it gives me. It doesn’t always feel like work, but sometimes it is rough. I don’t come from economic capital, so there have been five years of a lot of labor. I’ve come to the point now where, for the first time in my life, I live over the poverty risk line so I can take a fucking month off. I had a feeling last year where I was like, “Fuck. I don’t know what I’m doing.” I’m just producing concept, concept, concept. I need a free month to actually absorb where this world is going.

Have you run into any difficulties getting your art recognized in the German art scene?

I did actually have my first successes in France rather than in Germany, which is funny. I had a lot of shit from old white feminists telling me that I was reproducing objectification of Albanian women when I was doing my first works, [“Tales of Lipstick and Virtue”, 2013-2018]. It’s funny that [we have] this image of the old white man gatekeeping, but sometimes the old white feminist is much worse than the old white man. At the same time, Berlin is a really open place as a Western capital for artists. At a very young age, I found great gallery representation because people are actually open to listening and open to seeing what’s happening.

It’s a global phenomenon that there is a big gap between who the people in power are and who the people are that make work. I was lucky to work with great people, but I’ve also been in situations where a jury is telling me that I’m too confident for my life story. People want you to cry in black and white and victimize yourself, and then you can have success in their institution. It’s a balancing act between acknowledging that, yes, we do have a lot of visible change, but we still have a lot of work to do in regard to structural change.

I’m trying to collaborate and invite, because I know that in many places in this world, I’m considered to be white. I live in Germany, which is one of the most industrialized places, and I do have a lot of access to spaces my collaborators don’t have. I profit from the suffering of my collaborators through the structures that maintain us, so I can also share the cultural capital that I have. I love collaborating as a practice but also, I have access to a space. I can invite somebody in. I might not come from money, but I can still have little hacks of fucking the system from within.

Chris Erik Thomas is the Digital Editor of Art Düsseldorf. They work as a freelance writer and editor in Berlin and focus primarily on culture, art, and media. Their work can also be seen in Highsnobiety, The Face Magazine, and other publications.