Milja Laurila is Using Old Medical Images to Reclaim the Gaze

Words: Chris Erik Thomas.

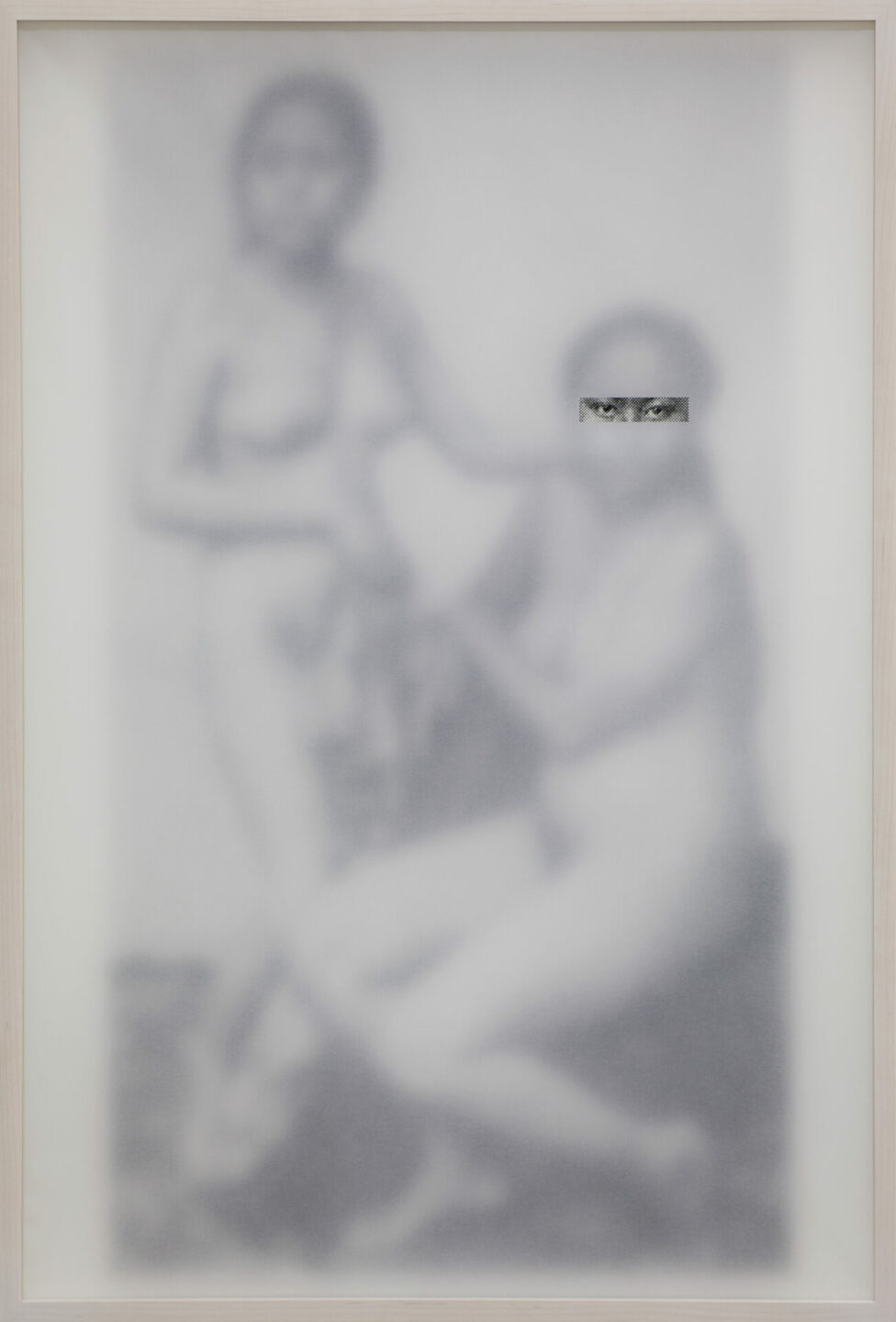

For the last five years, whenever Milja Laurila sat down at her desk to work, one massive book has been within arm’s reach. Aptly titled Woman: An Historical Gynæcological and Anthropological Compendium, the relic was first released in Germany in 1885 before receiving a major update in its eleventh version in 1927 that added a wealth of supplementary material and photographs. Spread across three volumes and totalling 2092 pages, the tome attempted to explain the mystery of women within a scientific context. Unfortunately (but unsurprisingly) the result was a sexist, racially-tinged look at women through a leering, predatory gaze. Around 100 photographs are contained within its pages that depict “native people” standing nude and staring into the lens of the white, colonialist photographer.

For Laurila, it has been a revelatory discovery. After stumbling upon the book by accident while deep in research for another project in 2017, she has come back to it again and again; most recently, using it as the basis for her “Untitled Women” series, which was exhibited at Persons Project during Gallery Weekend Berlin in June. The magnetic draw that the book has had on Laurila should come as no surprise to those familiar with her oeuvre. For decades, the Finnish artist has looked to old photographs for inspiration, especially those found in old scientific books and encyclopedias; pulling from the past, she often recontextualizes images mired in the racism, sexism, and bigotry of their eras by filtering them through a modern lens.

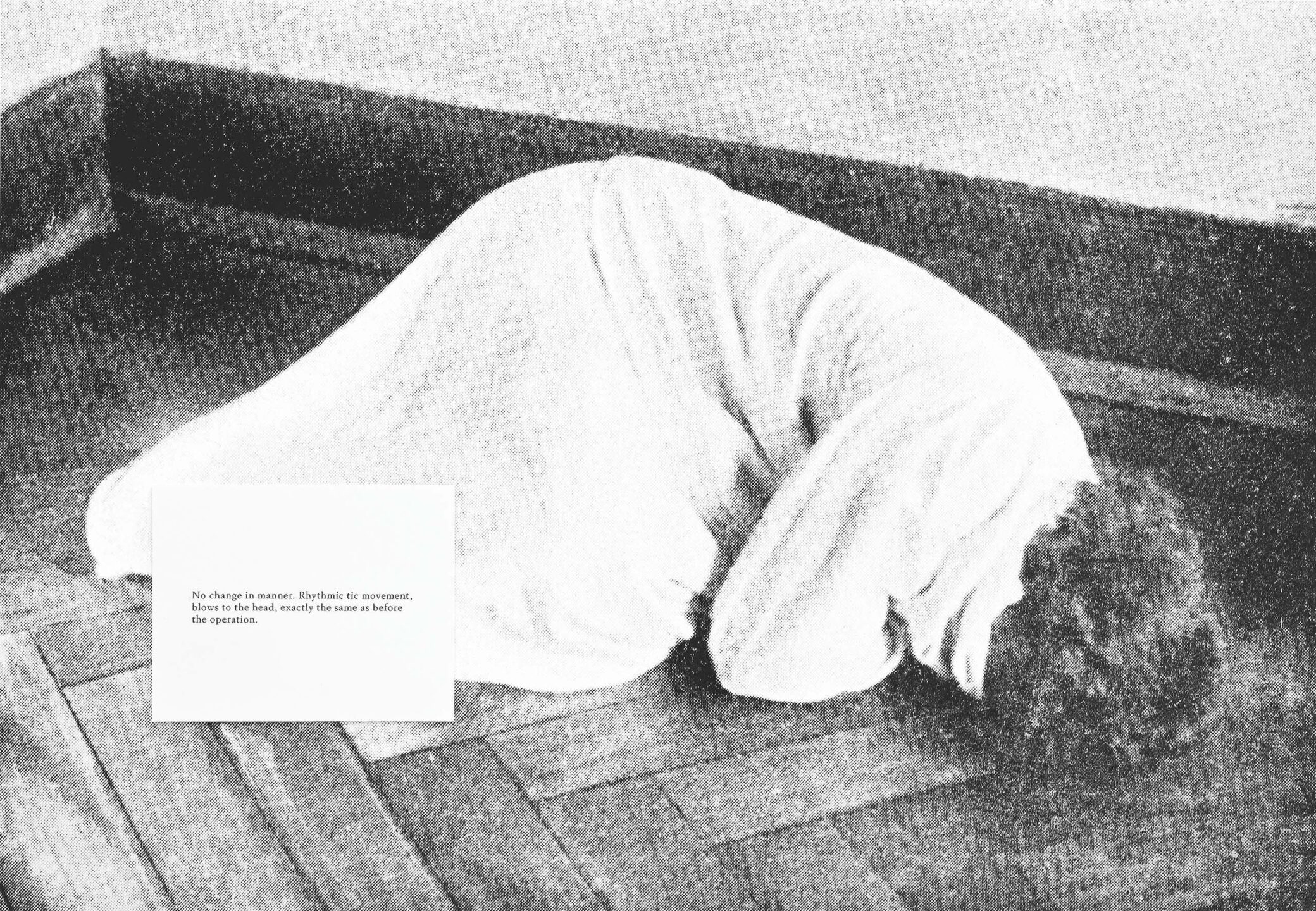

Milja Laurila. "Atlas und Grundriss der Psychiatrie (Blows to the head)", 2013. Archival pigment print, Diasec. 60 x 90 cm. © the artist. Courtesy: Persons Projects.

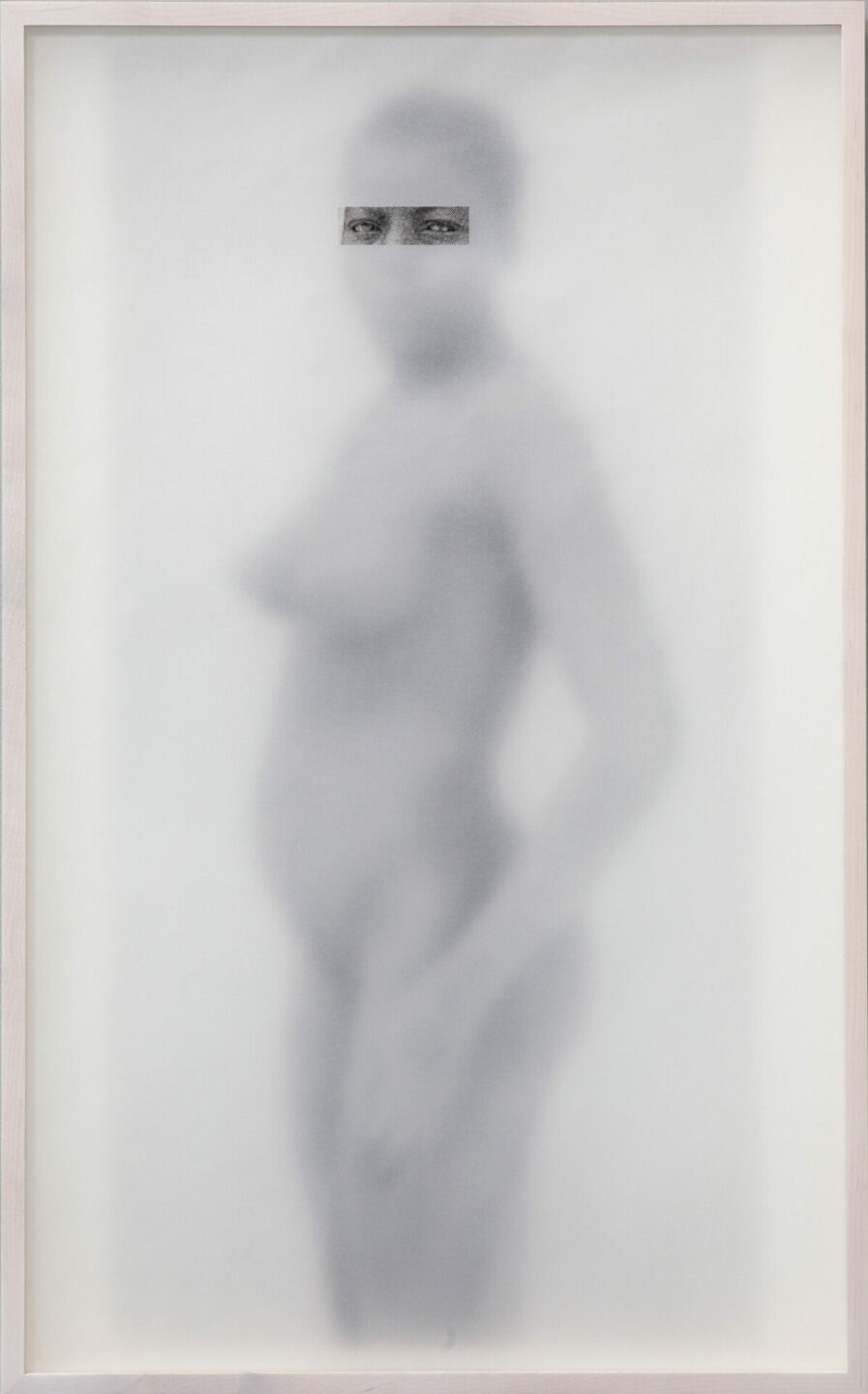

Milja Laurila. "Un Beau Spécimen", 2016. From the series "In Their Own Voice". 5 UV-prints on acrylic glass. 87 x 204 x 15 cm. © the artist. Courtesy: Persons Projects.

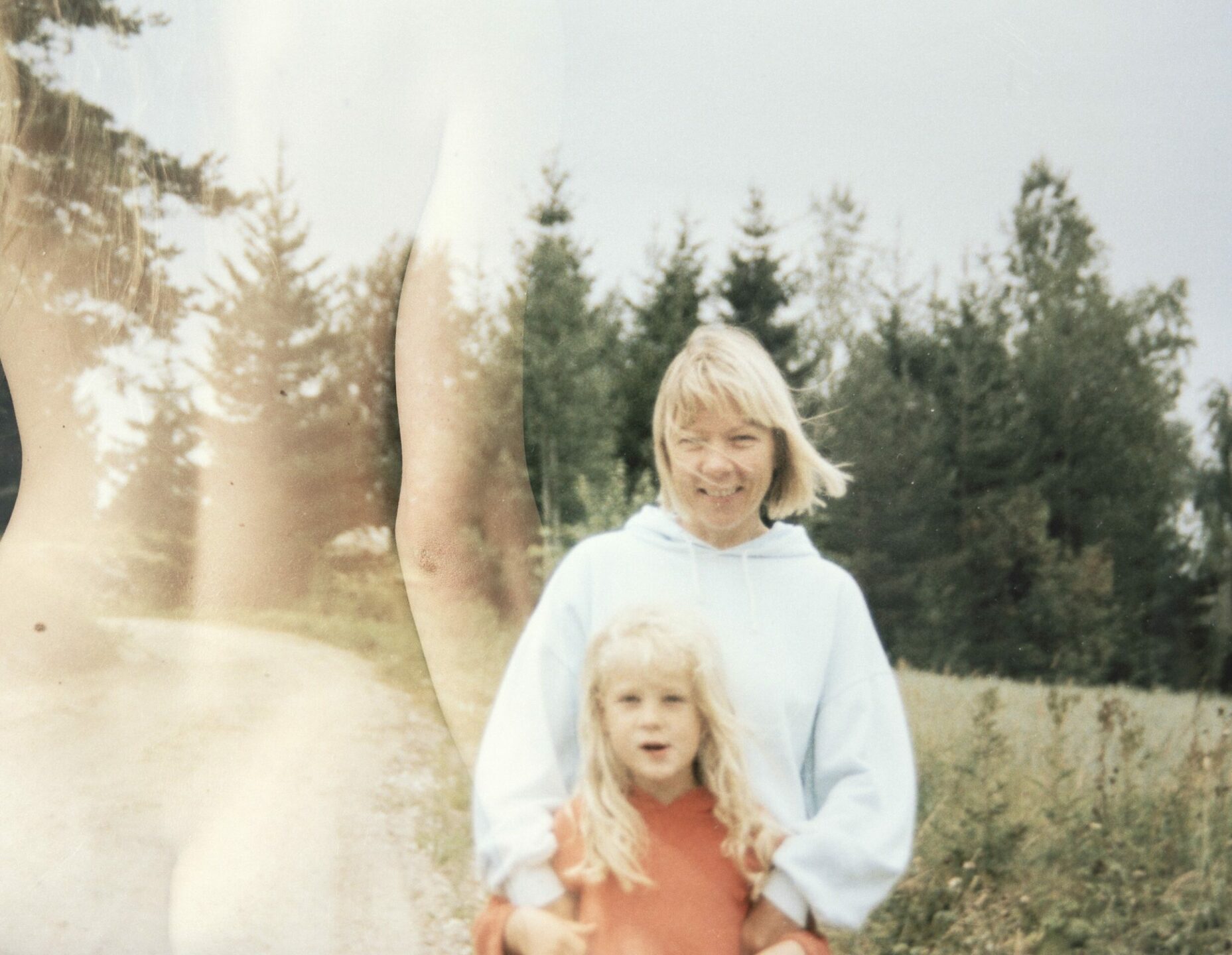

The practice has also allowed the artist to navigate her own history, as well. In her first series, (“To Remember”, 2004), she focused on her early childhood in Tanzania where she lived from ten weeks old until she was four years old. With no real memory of this period, she sourced images taken by her father, an amateur photographer, and combined them with new ones using double exposure. The result was a series that melted the divide between past and present, providing an early throughline that has united her works in the years since.

Laurila’s piercing interrogations of found photographs have formed the basis for series’ on everything from femininity and the scientific gaze (“In Their Own Voice”, 2016) to the reevaluation of mental disease and what defines normality (“Atlas und Grundriss der Psychiatrie”, 2013). With over a decade of experience trawling through history, she has produced a captivating body of work that digs into the ethics and power dynamics of photographic history.

As the artist continues her search for inspiration and prepares to develop new work, we called up Laurila for a video chat to discuss the “Untitled Women” series, reclaiming the gaze, and the violence women still face within the medical field.

Milja Laurila. "Untitled Woman V", 2021. From the series "Untitled Women". Archival pigment print mounted on aluminum, cut paper. 87 x 54 cm. © the artist. Courtesy: Persons Projects.

Milja Laurila. "To remember (mother)", 2004. Analog c‐print on aluminium. 62 x 80 cm. Courtesy: Persons Projects.

Milja Laurila. "Untitled Woman VII", 2022. From the series "Untitled Women". Archival pigment print mounted on aluminum, cut paper. 86 x 58,5 cm. © the artist. Courtesy: Persons Projects.

The relationship between women’s bodies and the medical field doesn’t seem to be getting any better. Just look at the abortion restrictions in the US. What do you think of these modern developments?

That’s a really good question because what I want to say with my work is that it’s not just history. Maybe it’s easy for some people to look at the pictures and think, “Oh, but this is 100 years old.” Actually, the same thing is still going on. It’s relevant today. Of course, I’ve been appalled at what’s happening in the United States, but there’s also a global phenomenon of this hatred towards women. Always trying to control their bodies and sexuality.

One thing that I’m interested in — which is not in the “Untitled Women” series particularly — is how we don’t know that much about women and women’s diseases. If women go to a doctor, then they can easily get prescribed some antidepressants because the doctors don’t know what’s going on. Women get easily misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed. I recently read an article in The Guardian about a study that found that when there is an operation, if the patient is a woman and the surgeon is a man, the woman is more likely to die.

One of the themes of your work is reclaiming the photographic “gaze” and tapping into how it feels to be looked at. In the “Untitled Women” series, only the eyes of the subjects can be seen. How did you come up with this concept?

I can’t say that it’s one thing. I’ve always been interested in the gaze. Before I went to study photography, I studied at the University of Helsinki and studied communication and film, so I read about the gaze like 20 years ago. In my previous work, I’ve used a lot of images of the backs of women so you don’t see the face or the eyes. In these medical books, if the woman is facing the camera, there’s usually this black or white box over their eyes so in this book, “Women”, it was really surprising that they were looking back at you. I was really, really taken by this. They were actually looking at me, and they had a really strong, powerful gaze.

That drew me to this book, and I wanted to focus on this — that they are looking back at you and how it makes you feel. In these medical books, you would think that the eyes are blackened to protect the anonymity of the patients, but then I thought that it’s also done for the viewer — for the male who is looking. He doesn’t have to face the woman and doesn’t have to look at her and see who she is. It’s the opposite in the “Untitled Women” series. She is actually looking at you.

Chris Erik Thomas is the Digital Editor of Art Düsseldorf. They work as a freelance writer and editor in Berlin and focus primarily on culture, art, and media. Their work can also be seen in Highsnobiety, The Face Magazine, and other publications.