Enter Andreas Schmitten’s Multifaceted, Miniature Worlds

Words: Chris Erik Thomas.

As an only child growing up in the 1980s, Schmitten was drawn to both the act of making small-scale models and to the wonders of the Abteiberg Museum in Mönchengladbach, as he wandered its halls and took in the sight of the sculptures it housed. It was this combination of influences that would eventually lead him to pursue a career in art that has brought his work to institutions in Germany and abroad.

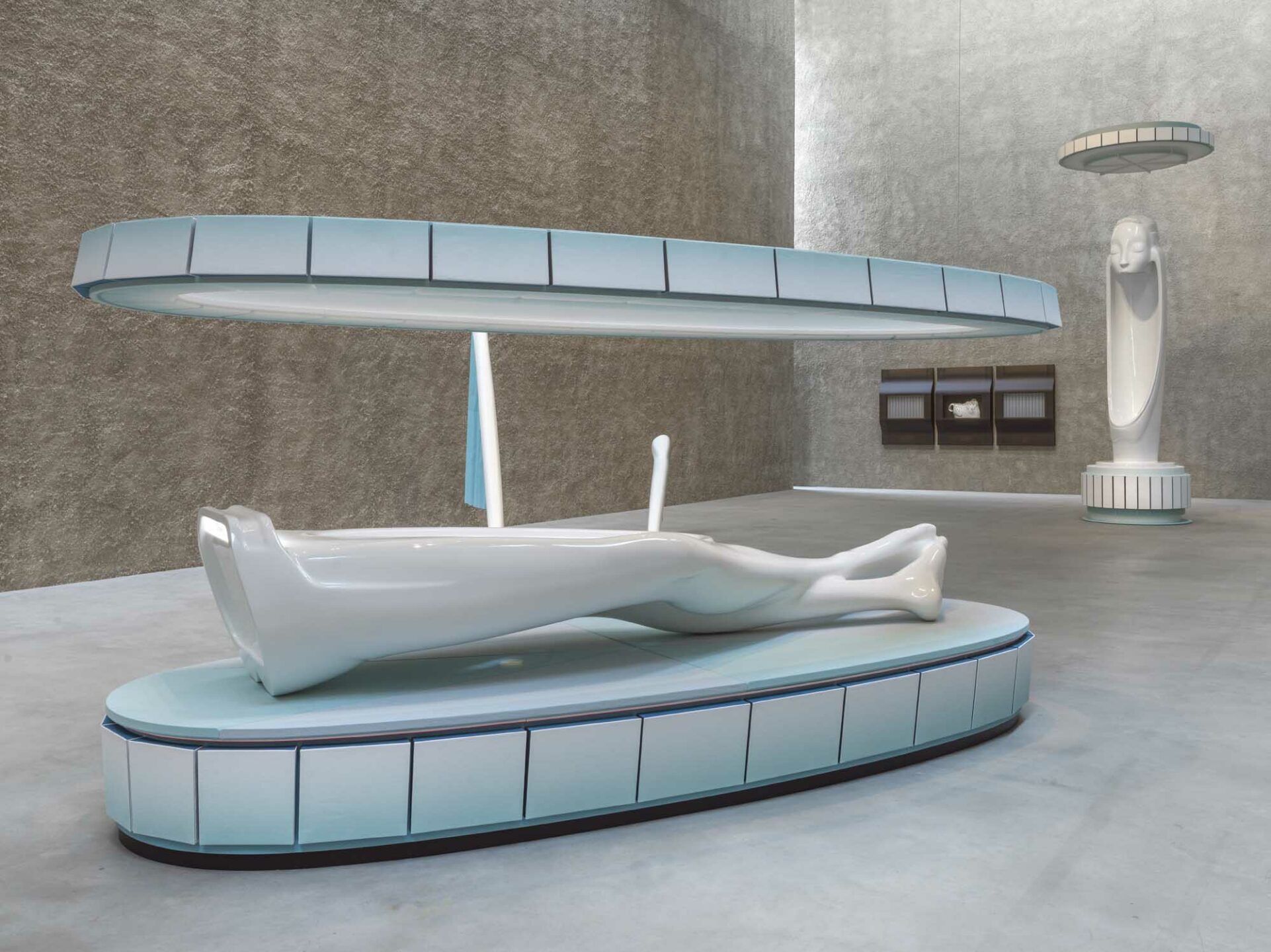

Seeing Schmitten’s work, it’s immediately clear why he has become such a beloved artist. He is capable of crafting everything from darkly comedic storyboards that strike at the existential fear of inclusion and emptiness (“First there is a house, then there is no house, then there is,” 2018) to sculptures of hypersmooth, almost alien vessels that merge humans with basins and other objects (the “SESSHAFT” exhibition, 2021). Throughout his entire oeuvre, there is a playful element that blunts the edges of even the darkest subject matter as he confronts themes of religion, history, and humanity. The end result offers the illusion of simplicity in the final pieces that belies an intricacy of form; a nearly artificial sheen masks the incredible scope of labor involved as he saws, sews, and casts the materials that make up his sculptures.

With representation by both König Galerie and SCHÖNEWALD, Schmitten has established himself as an essential artist in the contemporary art world of the Rheinland and beyond. On Friday, July 29 at 6 PM CEST, he will be part of König Galerie’s limited-time, 72-hour-only drop of part of the edition “Chimera Electrified”, based on drawings from a book of the same name. As he prepares for this drop, we spoke to the artist via email about his enduring love for models, learning about culture and time through sculpture, and the lessons he learned from the writing of French philosopher Gilles Deleuze.

Andreas Schmitten. "Chimera Electrified", 2022. Print and coloured pencil on cardboard

mounted on Canson Paper. 41.6 x 32.2 x 4 cm. Unique, signed, and hand-finished. Courtesy of König Galerie.

As a child you began to make models quite obsessively and, decades later, they are still a part of your artistic practice. What is it about creating these miniature scenes and spaces that draws you in?

My first works are models of spaces, but it was important to me to see these as independent and completed works; they were not reproductions of something but an exploration of the idea of making a model and of space as a form of expression.

It was important to me to question and explore where the practice of model making and miniatures comes from and what approaches there are to it — particularly outside of an art context. My affinity for models and miniatures corresponds to children’s play because all stuffed animals, Lego, Playmobil, building blocks, and action figures are always models of an adult world. But with them, spaces of their own are created that develop a pull effect and in which this adult world becomes irrelevant for the children who are playing. I see this not only in children, but also in model trains, in model-making hobbies. With my grandmother, for example, it’s the porcelain elephants.

This is where my thoughts about the specifics of the model come from. My work attempts to explore the materials and procedures of model building. What fascinates me is the pull of the model space, which becomes so strong that it no longer matters where and in which real space I am. Similar to a film scene, a miniature space is created, but in contrast to the film, this space is real, even if it is too small. I see retreat or escape from reality in the love for the model, inherent in the dream of a submissive and controllable world.

For many artists, there was an exhibition or museum they attended in their adolescence that sparked the desire to become an artist. You’ve talked about going to the Abteiberg Museum in Mönchengladbach as a child, but I’m curious if there was any specific exhibition that you saw which inspired you?

No, there was no specific exhibition that was the deciding factor in wanting to become an artist. Instead, it was the place itself that had an impact on me — especially the architecture of Hans Hollein. In my childhood imagination, the museum and the exhibited sculptures were an indoor playground or labyrinth with special rules and objects. This led me to the Abteiberg again and again.

Andreas Schmitten. Installation view of "Sesshaft", 2021. Photo by Roman März. Courtesy of König Galerie.

Andreas Schmitten. Installation view of "Sesshaft", 2021. Photo by Roman März. Courtesy of König Galerie.

Your work often interrogates the functional, everyday objects that humans create — particularly the culture and mythos built up around these objects. Where did this fascination with these seemingly mundane objects begin? What continues to draw you to them?

You can learn a great deal about the contemporary [world] and all its facets through how these mundane things are created. This is actually like a classical sculpture; you can learn a lot about culture and time from the form [of the sculpture].

One facet of the art world that is still in its infancy is NFTs and the concept of the “metaverse.” As a sculptural artist, does this new virtual frontier attract you?

I am observing it, but so far, I can explore the ideas I am pursuing with my current techniques and materials.

Your 2018 work, “First there is a house, then there is no house, then there is”, feels eerily prescient coming before the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic initially seemed to offer the world a refresh, but now things seem back to normal (or worse). How did the pandemic shift your mindset? Did it alter your artistic practice at all?

Yes, definitely. For me, it was similar to being confronted with a war or other drastic global events. As a result, I couldn’t continue with the pieces I was working on at the time.

The beginning of the pandemic was the occasion for me to find an answer to the question of how history is constructed. How does something become part of the history of art or architecture? History is always something made; everything that is not conserved disappears, falls out, and does not become part of history. History is based on constructed causal chains. Through the pandemic, we are part of a global event and can witness how this event will be historicized. I wonder how we could narrate history differently? There is also the question of what role our bodies play in this. This becomes particularly clear in a pandemic that affects people’s bodies.

For example, one of my sculptures from 2018 is titled “1986.” This is the year we were confronted with the Chernobyl disaster. Others are titled “Fragile Construction”, which is a reference to our model of life. When Corona came, it undoubtedly changed these works — especially the view of them.

Andreas Schmitten. "First there is a house, then there is no house, then there is“, 2018. Photo by Andreas Fechner. Courtesy of König Galerie.

Andreas Schmitten. "1986", 2018. Wood, cardboard, plastic, various materials. Photo by Andreas Fechner. Courtesy of König Galerie.

The writing of French philosopher Gilles Deleuze attracted you during your studies of philosophy. He believed that the task of art is to create “signs” that push us out of our habits of perception and inspire creation. How does the work of Deleuze inspire you and your art?

Important for me was his idea of the impossibility to express the most important things with language and his powerlessness facing art, even though he was such a great thinker. That made a deep impression on me. .

When were you first introduced to König Galerie? How has the working relationship been?

That was probably in 2015 or 2016. Since then, we have realized many projects together and I very much appreciate the commitment on the part of the gallery. Above all, I am fortunate to work with a gallery owner who is of the same age and yet very experienced.

The material you create works with is often a bit of an optical illusion. For example, sculptures that look like porcelain are bronze sprayed white. How do you go about picking the materials you work with?

Shrouding and surface always come to mind when I think about a sculpture and there is the requirement of durable material. But, in principle, the idea dictates the material.

Chris Erik Thomas is the Digital Editor of Art Düsseldorf. They work as a freelance writer and editor in Berlin and focus primarily on culture, art, and media. Their work can also be seen in Highsnobiety, The Face Magazine, and other publications.