Franka Hörnschemeyer Explores the Materiality of Things

Words: Chris Erik Thomas.

This is the mantra that guides the work of Franka Hörnschemeyer. Since entering the art scene in 1989, the artist has made a name for herself with both her sculptural works and her massive, room-filling installations in which visitors wind their way through a labyrinthine maze of visual sensations. Her 2001 work “BFD – bündig fluchtend dicht,” a spatial sculpture constructed of red and yellow iron rods that occupied one of the northern courtyards of the German Bundestag, caused a particular stir on the international art scene.

For Hörnschemeyer, the key to unforgettable art lies not only in the concept, but also in the materials. Her work is in constant dialogue with an idea of Franz Kafka’s, that every person has a space within them. “Sculpture for me is about exploring unexpected relationships between materials,” she says. “In fact, I consider myself a material as well.” Sculpture is a medium that explores unexpected relationships between materials.

As Galerie m presents work by Hörnschemeyer in booth A-03 at this year’s Art Düsseldorf, we spoke with the artist about her work as a professor of sculpture at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, the importance of misunderstandings, and her lifelong passion for exploring bodies and space.

Franka Hörnschemeyer. "Aktenkeller 1", 1994. plasterboard, paper, wood. 37 x 40 x 13 cm. ©Franka Hörnschemeyer, Courtesy Galerie m, Bochum.

What message do you want viewers to take away from the art you’re showing at Art Dusseldorf?

At the moment, I don’t think anyone can escape the geopolitical situation, the war, the environmental crisis, and the pandemic. My work, like the work here at the fair, explores boundaries and revolves around the question of the relationship between body and space and the relationships between things and people. I think that information is much more crucial to the world’s appearance than matter. Information is what’s in-between, the relative space between matter.

You can explore where the material comes from, what it’s made of, how old it is and how it will evolve, and what psychological and social aspects it has. And I deal with the conditions of space in the same way. I believe that there is no difference between body and space. Body is space and space is body. That is my tool for perceiving the world, and that is what I want to pass on.

What inspired the works you have on view at Art Dusseldorf

Our view is culturally shaped and we experience our environment through our body. In my works, I give directions, directions of movement, and directions of vision. Spaces are seemingly separated or connected by a channel that simultaneously transmits and receives. Their texture is related to our location and at the same time to our sensations and memories, our reality. That certainly has to do with form; the boundary is the form. I am concerned with questions like: What is in front and what is behind? How do I get from here to there, and how can I change sides? It’s been my experience that many people are content to focus on the surface. I’m more curious about what lies beneath or behind the surface.

Information is what’s in-between, the relative space between matter.

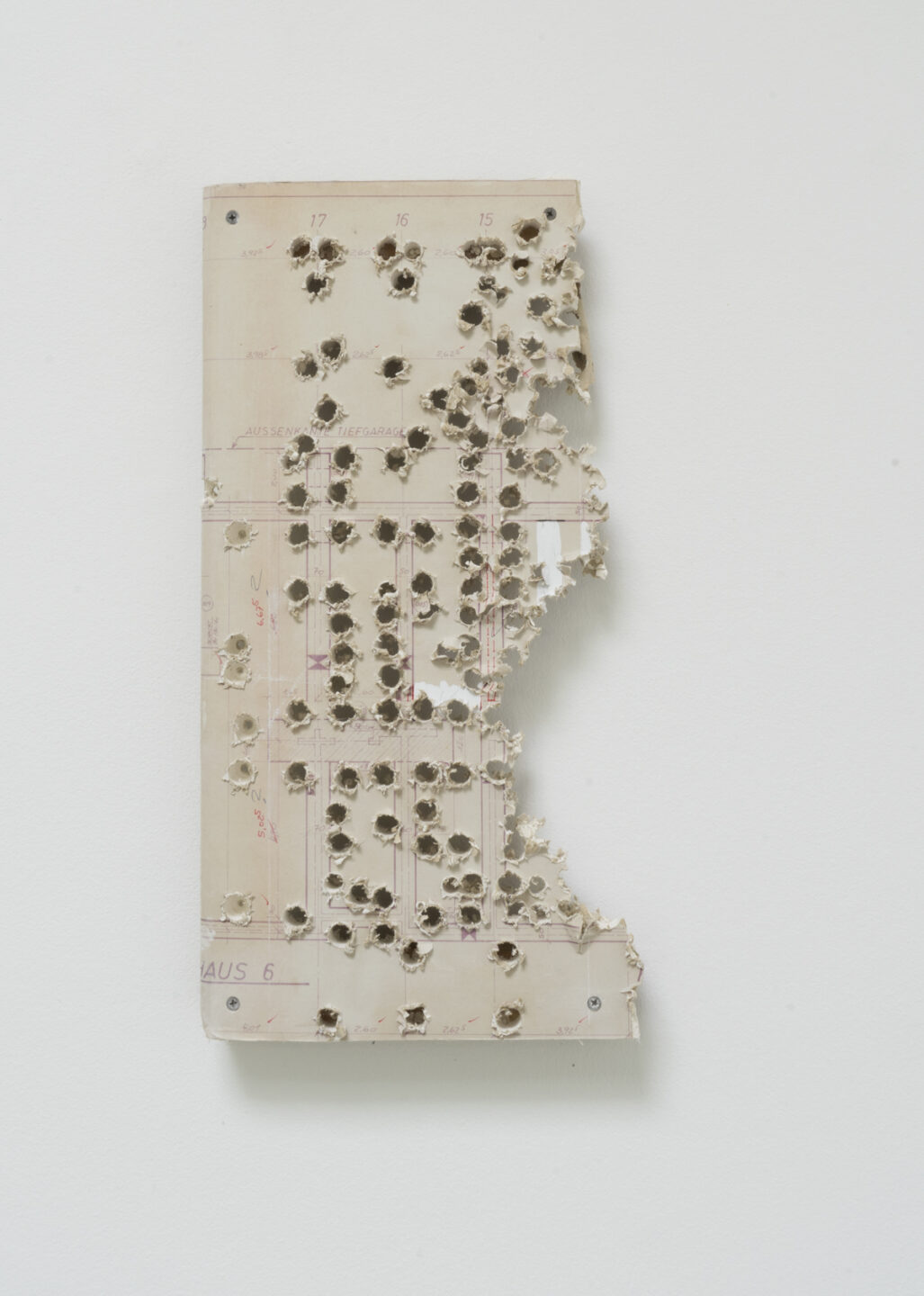

Franka Hörnschemeyer. "House 6", 1993. plasterboard on wooden slats. 52 x 26 x 4.5 cm. ©Franka Hörnschemeyer, Courtesy Galerie m, Bochum.

How has your artistic practice adapted to the pandemic?

I am fortunate to be able to continue working in my studio. The retreat from the public to the private sphere and postponements of exhibitions due to the pandemic has not significantly affected my artistic activity. I see the pandemic as an effect of a deeper cause, rooted in human behavior, in our interactions with each other and with nature. As I explore questions about relationships in space, the pandemic has also changed my work. When spaces are abandoned, traces of presence remain; they store time and are constantly changing in the process.

How important are art fairs for you as an artist? Has that changed at all because of the pandemic?

Art fairs are a place where art is traded, a place that follows certain rules. While I am interested in rules, systems, and structures, I tend to go to museums, art institutions, and galleries to experience art. Being unable to experience these places, because they were closed so often due to the pandemic, was regrettable.

How did you get involved with Galerie M?

In 2019, I showed the room-sized work “Opak 519” during an exhibition at the Museum unter Tage in Bochum, where I met the gallery owner Susanne Breidenbach. Since then, an intensive and constructive collaboration has developed.

Franka Hörnschemeyer and gallery owner Susanne Breidenbach in the exhibition "Axiom 421" at Galerie m, Bochum 2021. ©Franka Hörnschemeyer. Photographer: Donat Schilling. Courtesy Galerie m, Bochum.

When spaces are abandoned, traces of presence remain.

Franka Hörnschemeyer: "Opak 519" at Museum unter Tage, Bochum 2019. shell elements, anchor cables. 415 x 970 x 1314 cm. ©Franka Hörnschemeyer. Photographer: Donat Schilling.

What initially attracted you to the medium of sculpture?

I have been interested in space since I was a child and was curious about how spaces can change me and how I can change them. In doing so, I never distinguished between body and space, and I still use these experiences in my sculptural work today.

You also work as a professor of Sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts Düsseldorf. What is the most important lesson you try to teach young artists?

In the Academy, we talk about expanding the possibilities of our means, everything can be important for this, and there is no certainty. We do not know beforehand where we are going and prefer to stay in unknown territory, because we recognize only what we know.

Also, what is one of the biggest misconceptions about the art world that you try to dispel with your students?

For me, artistic exploration is communication, and gaps in knowledge are the basis for this, they are the factor for the exchange and supplementation of information. Gaps in knowledge give rise to misunderstandings, which can be placed side by side – even in a perspective shift. So I consider misunderstandings and misconceptions, big and small, even if they are unpleasant at the moment, as a condition for movement.

The meaning of a material lies in its origin, its history, its production, and its function.

Your work tackles the use of space and its relation to the human body. What is it about these themes that continues to attract you?

Essential to the development of my work are dialogues with the material, often materials such as formwork elements, plasterboard, or aluminum honeycomb, which are used for the precipitous construction of buildings. I converse with spaces, exploring idiosyncrasies such as the former identity of a place, operating not only on a spatial axis but also on a temporal one. The meaning of a material lies in its origin, its history, its production, and its function, and if you listen carefully, you learn a lot.

Kafka once said: ” Everyone carries a room about inside them. This fact can be proved by means of the sense of hearing. If someone walks fast and one pricks up one’s ears and listens, say at night, when everything round about is quiet, one hears, for instance, the rattling of a mirror not quite firmly fastened to the wall.”

I see sculpture as exploring unexpected relationships between materials. In fact, I also think of myself as a material. The relationship between materials oscillates, hence you can also be a piece of aluminum honeycomb looking at the world.

Chris Erik Thomas is the Digital Editor of Art Düsseldorf. They work as a freelance writer and editor in Berlin and focus primarily on culture, art, and media. Their work can also be seen in Highsnobiety, The Face Magazine, and other publications.