Prof. Dr. Susanne Gaensheimer on K21’s “Shifting Dialogue” Exhibition

Words: Chris Erik Thomas.

Prof. Dr. Susanne Gaensheimer isn’t afraid to take on art’s toughest questions. On the contrary, it’s what inspires her work as director of Düsseldorf’s North Rhine-Westphalia Art Collection. It’s now been nearly five years since she joined the museum and, in that time, she has been at the forefront of diversifying the works on view; successfully bringing more internationally-oriented positions on contemporary art to the stylishly curved building in the city’s old town district.

The shift in focus under her directorship is hardly a surprise given Gaensheimer’s background and accolades. After studying art history in Munich and Hamburg, she graduated from an independent study program at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art and secured her Ph.D. After some time spent as a freelance curator, a series of stints at museums around Germany followed, including the Westphalian Fine Arts Society in Münster and the Municipal Gallery in the Lenbachhaus in Munich. At the 2011 Venice Biennale, she was awarded the Golden Lion for Best National Participation for her curation of the German Pavilion and before taking her current position in Düsseldorf, she managed Frankfurt’s MMK Museum for Modern Art for eight years.

Now, with two distinct exhibition buildings in the state gallery (K20 and K21), Gaenesheimer has had plenty of space to expand the palate of both the museum and its patrons. Nowhere is that more apparent than with the bold new exhibition, Shifting Dialogues: Photography from The Walther Collection, which runs from April 9 through September 25. Curated by Artur Walther with advisement by the late Okwui Enwezor, the collection features more than 500 photographic works from Nigeria, South Africa, Kenya, Cameroon, Angola, the African diaspora, and Europe.

Ahead of the opening of the exhibition on April 9, we talked to Gaensheimer about the importance of confronting postcolonialism, the changing state of photography, and why the museum experience can never be replaced.

Prof. Dr. Susanne Gaensheimer, Director of the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen. Photo: Andreas Endermann, 2017. © Kunstsammlung NRW.

Museums are not only places of documentation and archiving. They are also dynamic actors that map, initiate, and shape contemporary discourses. To what extent does postcolonial criticism inform the exhibition?

In building the collection, Artur Walther was significantly advised by Okwui Enwezor, a pioneering curator and founder of postcolonial criticism in exhibition work. The two began acquiring their first works on joint trips to different countries in Africa. In 2010, the first large collection presentation in Neu-Ulm emerged from this. Many of the themes and artistic intentions that became visible in the first exhibition have been pursued by Enwezor and Walther while building up the collection. Thus, the exhibition at K21 where the collection is now on view has also been significantly influenced by Enwezor’s post- and decolonial thinking and actions.

How has the Black Lives Matter movement shaped the art and cultural landscape? Is decolonization primarily an issue or is it also a practice that affects acquisitions, target groups, or, for example, the reevaluation of collections?

The exhibition emerged from the discussions we had at the museum also (but not only) under the sign of the Black Lives Matter movement. What was particularly important to us with the exhibition was to make visible the historical developments of artistic activism that have produced groundbreaking photographic image projects since the 1940s. We present works by Seydou Keïta, Malick Sidibé, and Zanele Muholi, and show decolonial processes in their historical depth. At the same time, for several years, we have been in the process of expanding the museum step by step through new acquisitions and a polyphonic exhibition program, and Shifting Dialogues is a central component of the opening.

How has the collaboration with The Walther Collection been?

We value our collaboration very much. Artur Walther and I have been familiar with each other for some time, so working on a joint exhibition has mutually enriched us.

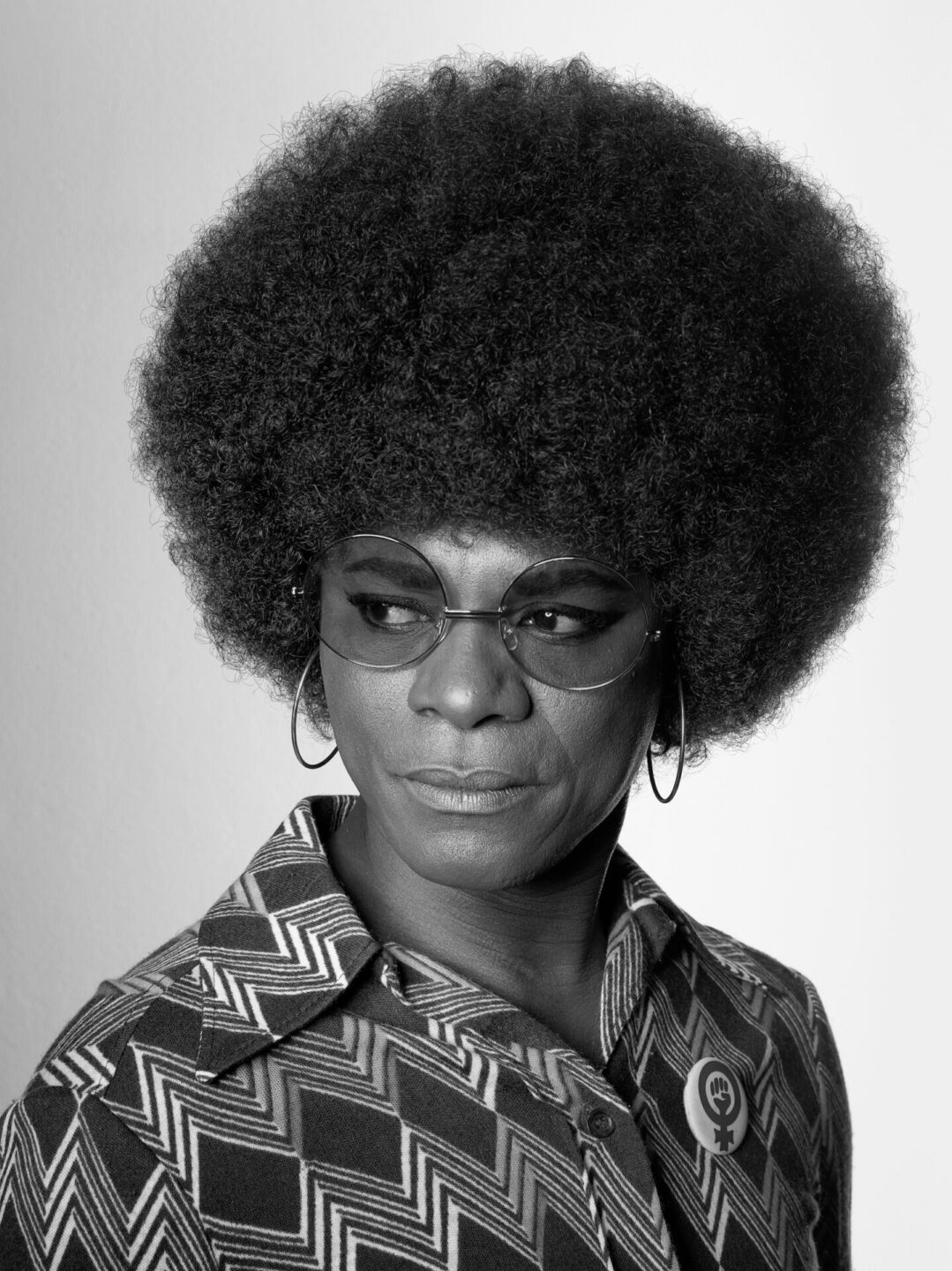

Samuel Fosso. "Self-Portrait (Angela Davis)", 2008. © The artist. Courtesy the artist, Jean Marc Patras, Paris and The Walther Collection, Neu-Ulm/New York.

Photographs can become an agent for developing, shaping, confirming, and disseminating notions of the self and self-images.

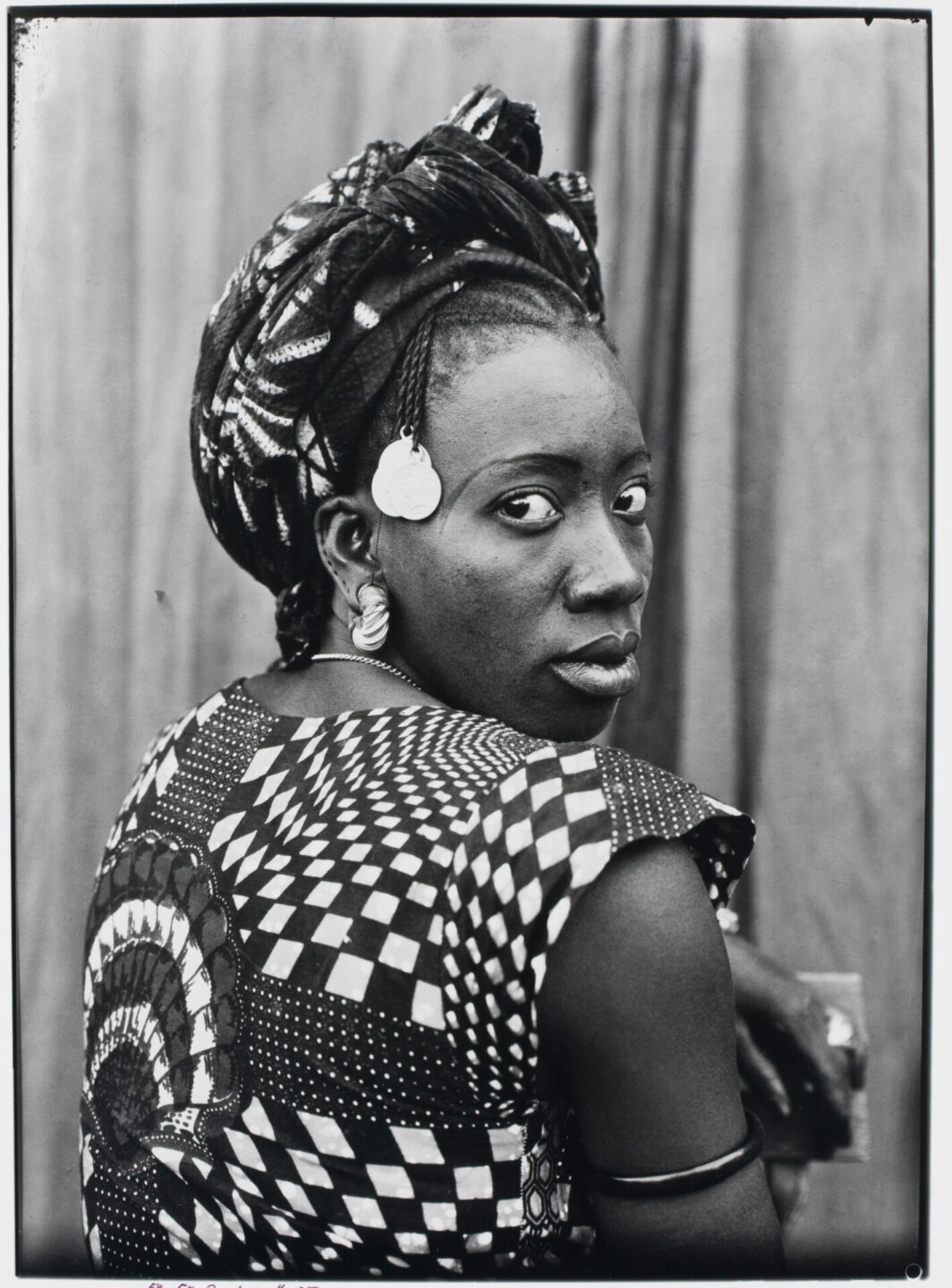

Seydou Keïta. "Untitled", 1952–1955. Courtesy CAAC - The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva and The Walther Collection, Neu-Ulm/New York.

How are historical and cultural transformation processes reflected in the medium of photography?

Photography is in a constant state of change. The exhibition shows how photographs can become an agent for developing, shaping, confirming, and disseminating notions of the self and self-images.

Okwui Enwezor stated in a conversation with Artur Walther in 2017 that: “I think that right now, photography – whether it’s in Africa, Europe, or elsewhere – is at a turning point. Photography is embattled. […] It’s embattled because photography is being overtaken, as a medium; it is being overtaken by technology and different forms of distribution.” This development has come to a head in recent years. How do you assess this?

Enwezor hits it right on the nose. Numerous new technological innovations have emerged in recent years. The concept of the image has continued to change. New technical [and] staging possibilities for artists are emerging. We are pleased to present in the exhibition works that have entered The Walther Collection only in recent years, including Mimi Cherono Ng’ok, Kudzanai Chiurai, Lebohang Kganye, and Sabelo Mlangeni. Their works show the facets of these processes of change.

Düsseldorf is a formative location for photography. How do works by Bernd and Hilla Becher, for example, which are also part of the Walther Collection, relate to the African works shown here?

We are showing the Bechers’ “Anonymous Sculptures” – as Enwezor did in 2010 – together in a room with works by Malick Sidibé and J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere. The juxtaposition reveals the importance of typological, taxonomic, and serial structures to global photography. It also reveals the complex and shifting interrelationships between social change, social identity processes, and artistic image production.

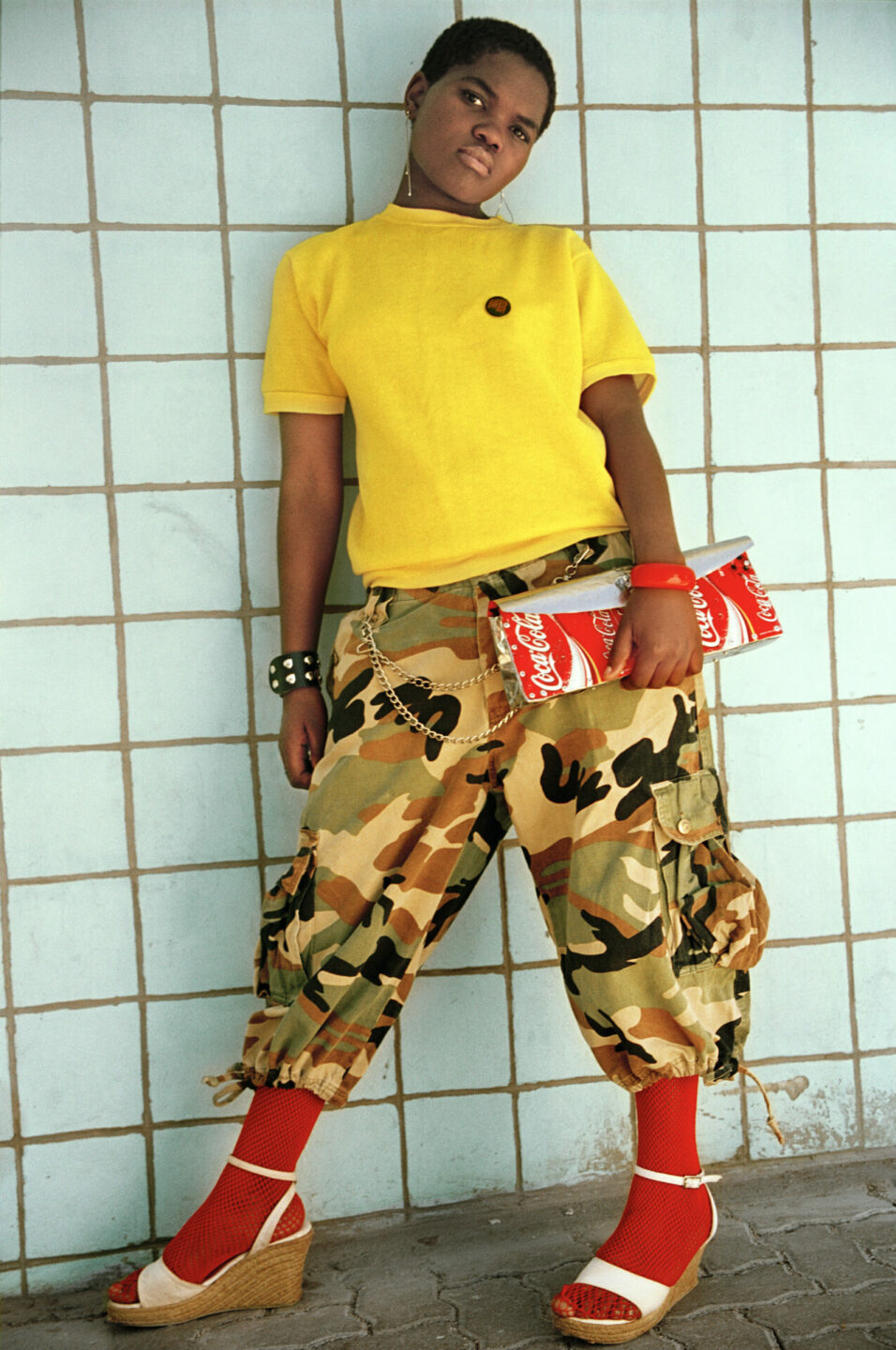

Nontsikelelo (Lolo) Veleko. "Nonkululeko", 2003. © The artist. Courtesy of the artist, Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and The Walther Collection, Neu-Ulm/New York.

The museum visit is not replaceable, but can be expanded and experienced in new or different ways.

Rotimi Fani-Kayode. "Untitled", 1987–1988. Courtesy Autograph ABP, London and The Walther Collection, Neu-Ulm/New York.

How do you think the experiences of the last two years will be reflected in artistic works?

That remains to be seen. Hito Steyerl has, after all, developed new major work in her exhibition at K21 – “SocialSim (2020)” – in which she has already addressed the pandemic from a sociopolitical perspective. This work has been acquired by the Kunstsammlung and will be on view in the K21 collection.

The pandemic has shown how important it is for cultural institutions to interact with their audiences in various ways. How has the art collection dealt with the situation over the past two years? What have you learned, and what are your plans for the future?

Before the pandemic, we developed a new website to serve as a platform for multimedia formats. At the beginning of the first lockdown, we launched this new website with a new moving image series, podcast seasons, and our multimedia storytelling tool, “K+ Digital Guide,” for current exhibitions. The experiences of the last two years have shown us that the museum visit is not replaceable, but can be expanded and experienced in new or different ways by thinking of the art experience in analog terms and digitally. We want to stick with that.

What do you hope the audience takes away from the exhibition?

A diverse and reflective view of the world.

Chris Erik Thomas is the Digital Editor of Art Düsseldorf. They work as a freelance writer and editor in Berlin and focus primarily on culture, art, and media. Their work can also be seen in Highsnobiety, The Face Magazine, and other publications.