Beyond Sustainability: Adapting the “Degrowth” Theory to the Art World

For the first edition of our new essay series at Art Düsseldorf Magazine, we asked a selection of writers to investigate issues related to Sustainability in the Art World. This essay by Leigh Biddlecome, an Italy-based writer, probes the way that the economic theory of “degrowth” can be adapted to the art world and redefined by artists as a means of moving beyond the current sustainability paradigm.

Edited by: Chris Erik Thomas, Digital Editor of Art Düsseldorf.

It seems fitting that when I started writing this piece, my computer immediately corrected “degrowth” to “regrowth.” It does not bode well that I’m compelled to teach the keyword to the spellcheck program. Yet, within the last decade, “degrowth” has gained traction within certain progressive economic and political circles as an alternative to classic models that depend on ever-increasing GDP figures to indicate progress.

Degrowth proponents argue for prioritizing social and ecological well-being — emphasizing hyper-local solutions while “reducing excess resource and energy throughput.” Specifically, they call for scaling down some sectors and enacting redistributive strategies to reduce global social inequality. In contrast to “sustainability” or “green growth” platforms, where growth can be decoupled from negative environmental impacts, the critique positions growth as “intrinsically not sustainable.”

To approach the implications of this theory for contemporary art and performance, one must first acknowledge how an artist might instinctively react to the term itself. Stripped of rationale and context, “degrowth” has the potential to alienate artists and culture workers. Its connotations might even pose an existential threat to those of us in the practice (and business) of generating ideas and creative output; “degrowth” could imply a stifling sameness, an exhortation against creation, or even aesthetic collapse.

But degrowth is not synonymous with stagnancy. The octogenarian American economist Herman Daly distinguishes between “growth” and “development,” explaining: “When something grows, it gets bigger physically by accretion or assimilation of material,” whereas “when something develops, it gets better in a qualitative sense.” Forms of development which encourage societal well-being are not antithetic to, but rather encouraged within, degrowth contexts. A reformulation of Daly’s metaphor for artists might attempt to reconcile the two; an artist may be just the right person to argue that certain forms of artistic accretion or assimilation are necessary and co-existent with qualitative development.

It is not enough to make art on “environmental themes.”

One of the most compelling arguments from degrowth economics that can be applied to the art world is redistribution. The writer John Cassidy, paraphrasing the 2019 Nobel in Economics winners Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo, explains: “When the benefits of growth are mainly captured by an elite, […] social disaster can result”. Given the economic reality of the contemporary art world, where a tiny proportion of artists garner the vast majority of earnings, some form of a degrowth redistributive model should attract significant support.

This theory also has implications for museums, aside from the obvious need to distribute funding more equitably. The researcher and interdependent curator Alessandra Saviotti offers these shifts to the current exhibition model: focus on developing fewer shows per year as a means of reorienting the “art-show-as-consumer-product” system; encourage deeper engagement by the public; and free up funding to support better conditions for artists in their creation process.

What might artists uniquely contribute to these concepts? We must reimagine the theory not simply for the context of art, but by a collective, creative imagining of arts practitioners. There are many possible routes for how this process of appropriation and re-definition might continue to unfurl, but two stand out.

Lara Fluxà. Installation view of “LLIM,” a collateral event at the 2022 Venice Biennale. Photo courtesy of Leigh Biddlecome.

When describing Catalonian artist Lara Fluxà’s “LLIM,” a collateral event at the 2022 Venice Biennale, the curator Oriol Fontdevila proclaimed: “this is not a site-specific intervention.” The “organism” Fluxà created involved a complex sculptural infrastructure, with up to 800 liters of Venetian lagoon water moving through its snaking PVC tubes and ouroboros-like glass Klein bottles blown by Fluxà (supported by master glassworker Ferran Collado). By contesting its site-specificity, Fontdevila implied that the work might reveal a kind of universality. In this way, “LLIM” demonstrates how the “hyper-local” component of degrowth theory might be complicated by artists deeply invested in their immediate environments and transnational comparative work. By using the theme of “silt” (“llim” in Catalonian), Fluxà departed from the parallel environmental damages to her native Catalonian marshes and then anchored herself in a collaborative undertaking in Venice, with its own reality of silt, lagoons, dredging, and environmental precarity — thus reducing the potential insularity of a “hyper-local” orientation.

Working with environmental scientists, activists, archivists, and local and Catalonian glassblowers, Fluxà created, as Fontedevila calls it, a “situated manifestation.” Specifically, it shows the challenge of defining a “steady-state” system, depending on scale and perspective. On an immediate level, it might appear to be a closed system of cisterns and tubes within the warehouse space. But lagoon water flows in and out, propelled by the movement of the tides and subject to any of the inputs to the canals themselves — from boat fuel oil stains and algae to silt from upstream rivers. “LLIM,” in its very design, demonstrates porousness and transformation across ecosystems, and an oscillation from what can be understood as the source (“cause”) versus the product (“effect”) within these systems.

Artists and cultural mediators are vital to any paradigm shift.

If we want to move the discourse from sustainability towards an arts-led form of degrowth, it is not enough to make art on “environmental themes.” That approach risks complacency within the viewer, artist, and curator, and a numbing repetition of the same tropes that bombard us daily from corporate branding and marketing. Instead, we need art as a “catalyst for destabilization,” a phrase inspired by language from Decentralising Political Economies (DPE), an ongoing open-source research platform. DPE highlights the ways in which art has the potential to question and act upon systems of labor and power through the creation of new infrastructures and protocols.

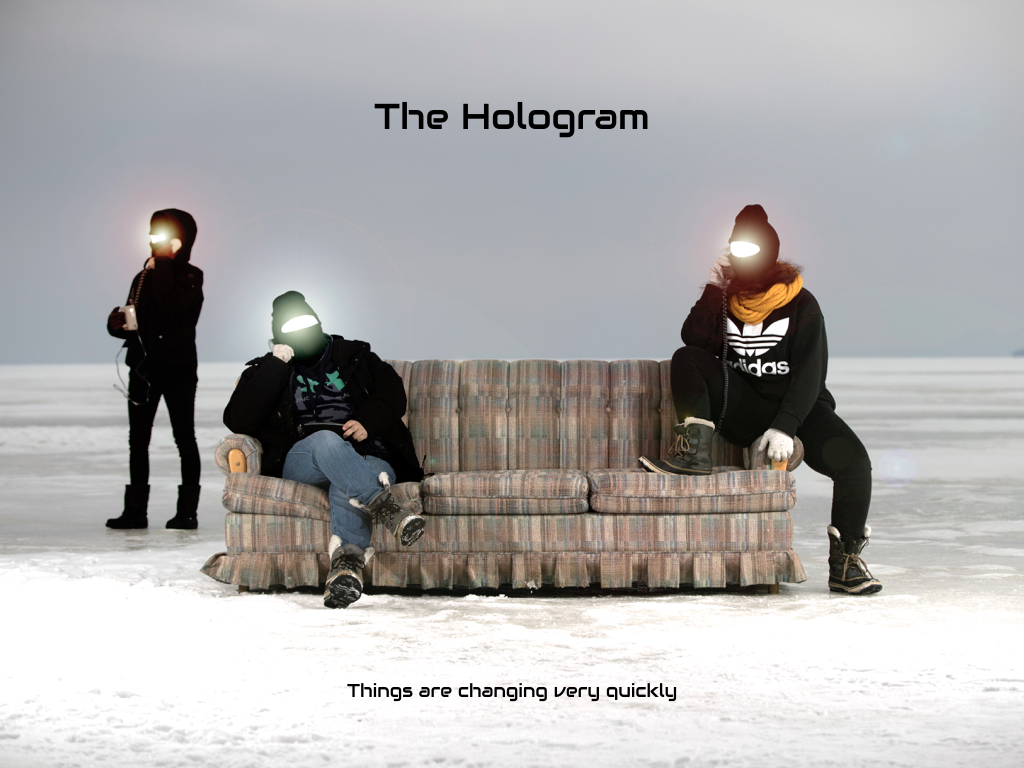

In some cases, like one of DPE’s partners, Arte Útil, it can also look like a refusal of traditional institutional infrastructure in its decision to remain unregistered and keep its online tools user- and artist-generated. Cassie Thornton, one of the artists featured in the DPE library, created The Hologram, a peer-to-peer feminist health network. It began as a “toolkit to exit economic precarity by attempting to build human relationships instead of accumulating goods and capital” within artists’ communities in Oakland, California, according to Saviotti. From there, the network developed further following Thornton’s engagement with the Greek Solidarity Clinics movement. Operating outside the traditional financialised health system, it offers an example of how an artistic approach can contribute to the degrowth movement by inventing new infrastructure out of a context of deeply lived experience in a form that is both an artistic practice and a project operating within communities out “in the world.”

"Holocourse 1 Trust." Courtesy of The Hologram.

Usually, economists and politicians reference art as a generic category within degrowth discussions, despite existing work by artists such as Thornton and Fluxà, which already prompts reconsiderations for this theory. If art is mentioned at all, it is in reference to the early 20th-century economist John Maynard Keynes, who proposed that the public will naturally turn towards art and nature once their fundamental needs have been achieved. While this is enchanting as a future vision, there’s a friction to its logic: it implies that art is a result of an economic process, a kind of leisure prize to be awarded once pesky basic needs have been taken care of.

Instead of positing the arts as a kind of “product” to be consumed following the satisfaction of basic needs, what if artistic creation was a catalyst for this new economically-sufficient world? Artists and cultural mediators are vital to any paradigm shift because of their potential to destabilize our perspectives, reorient our current focus on sustainability, and even develop new societal models. They should be considered necessary actors in the creation of this new system, rather than providers of its rewards.

Leigh Biddlecome is an Italy-based writer, translator, and curator of performance and visual arts in heritage spaces. As an Erasmus Mundus scholar, she received a joint MA in Heritage Studies and Development from EHESS Paris and ELTE Budapest in 2021.