Chasing Yesterday’s Parties: The Warholian Fantasy of An Art Scene

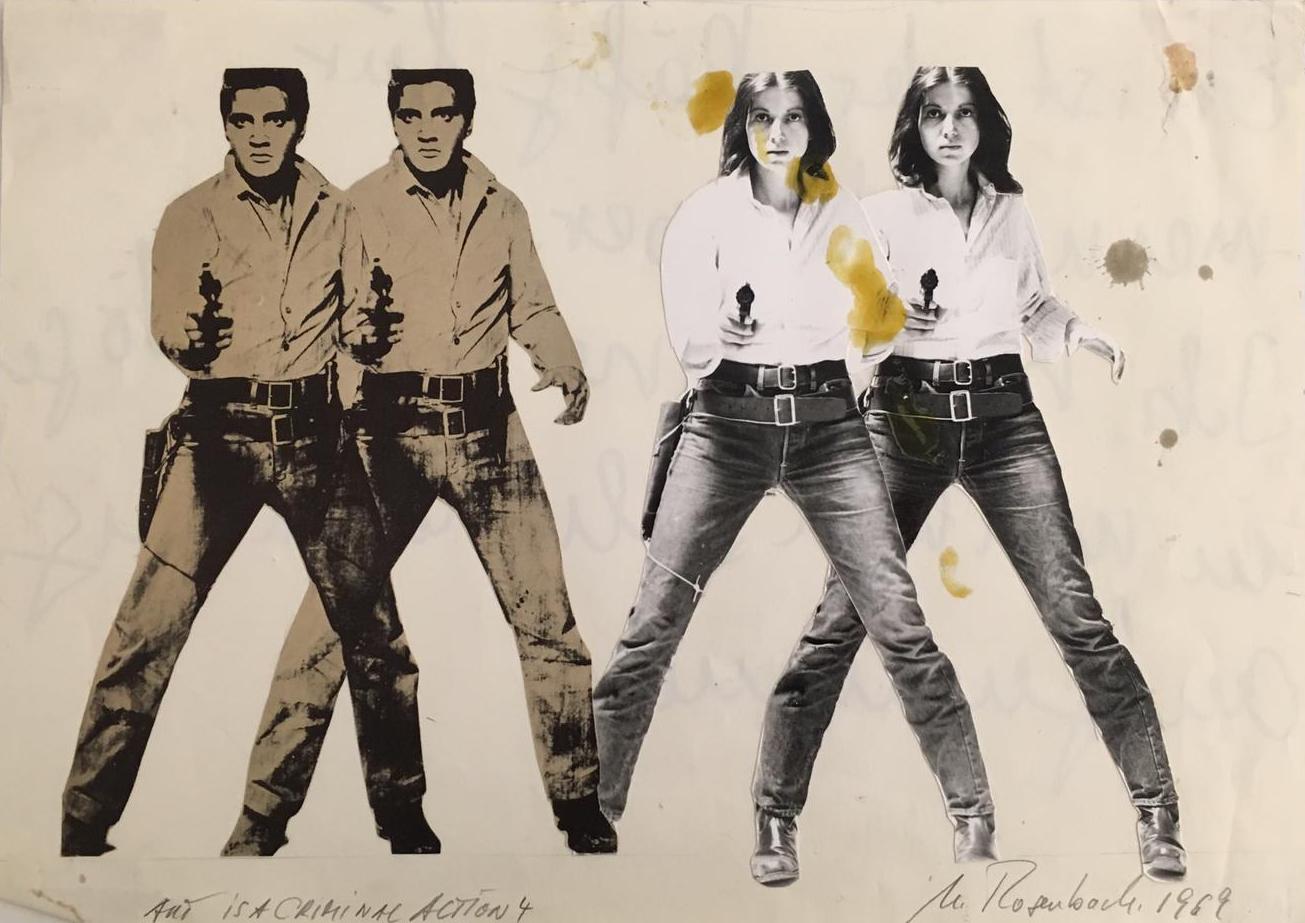

Ulrike Rosenbach. “Art is a Criminal Action 4”, 1969. Collage. 30 x 43 cm. Courtesy Priska Pasquer Gallerie.

As part of the offerings in our digital magazine, we’ve launched Dispatches From the Art World, a series of guest essays that investigate the latest and most fascinating opinions and trends shaping the industry. This essay by the Los Angeles-based writer Daniel Spielberger focuses on the artifice of manufacturing an art scene in the era of social media.

Edited by: Chris Erik Thomas, Digital Editor of Art Düsseldorf.

Sunglasses. Faded denim. Prada sweaters. White tanktops. They splatter paint on a canvas, venture into the neighborhood, and tag a fire hydrant as they irreverently smile and laugh. Back to the rooftop. Lanky models add finishing flourishes to the artwork — dashes of red, hazy gray fills a ghostly face.

Now, onto the next TikTok.

Aidan, a TikTok micro-influencer, has curated a feed of downtown cool. He and his friends wreak havoc at New York City Fashion Week and pay homage to Jean-Michel Basquiat with their subway graffiti. But the comments in the aforementioned video tell another story. “Fascinating to see art this passionless,” the user kiilerwhales writes.“Art where the goal is not in the piece itself, but in how one looks while creating it.”

With its seamless editing and filters, TikTok is perfect for crafting mini-narratives of our daily lives. Last year, the New York Times reported that there was a wave of artists on the app who have made thousands selling paintings for their followers by bypassing the gallery system for online stores. They use the platform to turn their work into an interactive experience, letting their audience in on how a painting goes from a sketch to a fully realized product. However, the Times also noted that more established types — such as Cindy Sherman — were wary of the platform, labeling it as “too gimmicky.”

This skepticism may stem from the platform’s inability to produce anything “cool.” As the aggressive commenter on Aidan’s TikTok noted, the performance element can come across as heavy-handed. Just as there is a customer base ready to buy a pop art rendering of Spider-Man, an army of skeptics are also eagerly waiting to attack any hint of artificiality.

Netflix’s new docuseries The Andy Warhol Diaries, which was released on the streamer in early March, chronicles how an artist’s “looks” became as important as their creations. Voiced by an AI-rendering of Warhol reading his own journal, the series shows how in the years leading to his death, Warhol used his clout as an artist to maneuver into the mainstream culture of the 1980s. He launched an MTV program; starred in an episode of The Love Boat as himself; did a Japanese videotape commercial. Even if his descent into commercialism earned him some scorn from the art world, his brand remained highly revered because he signified the Factory — an anarchic fantasy of creativity that reached its peak in the 1960s.

Within the span of three decades, his scene brought in the likes of Lou Reed, Candy Darling, Jean-Michel Basquait, and countless others. The Warholian mystique was a product both of the gallery system (he had close relationships with Uptown’s art dealers who bought and sold all this work) as well as his control of the means of communication. With the launch of his publication, Interview Magazine, in 1969, Warhol announced who was in and out — sidestepping the more established press outlets that were dismissive of the avant-garde.

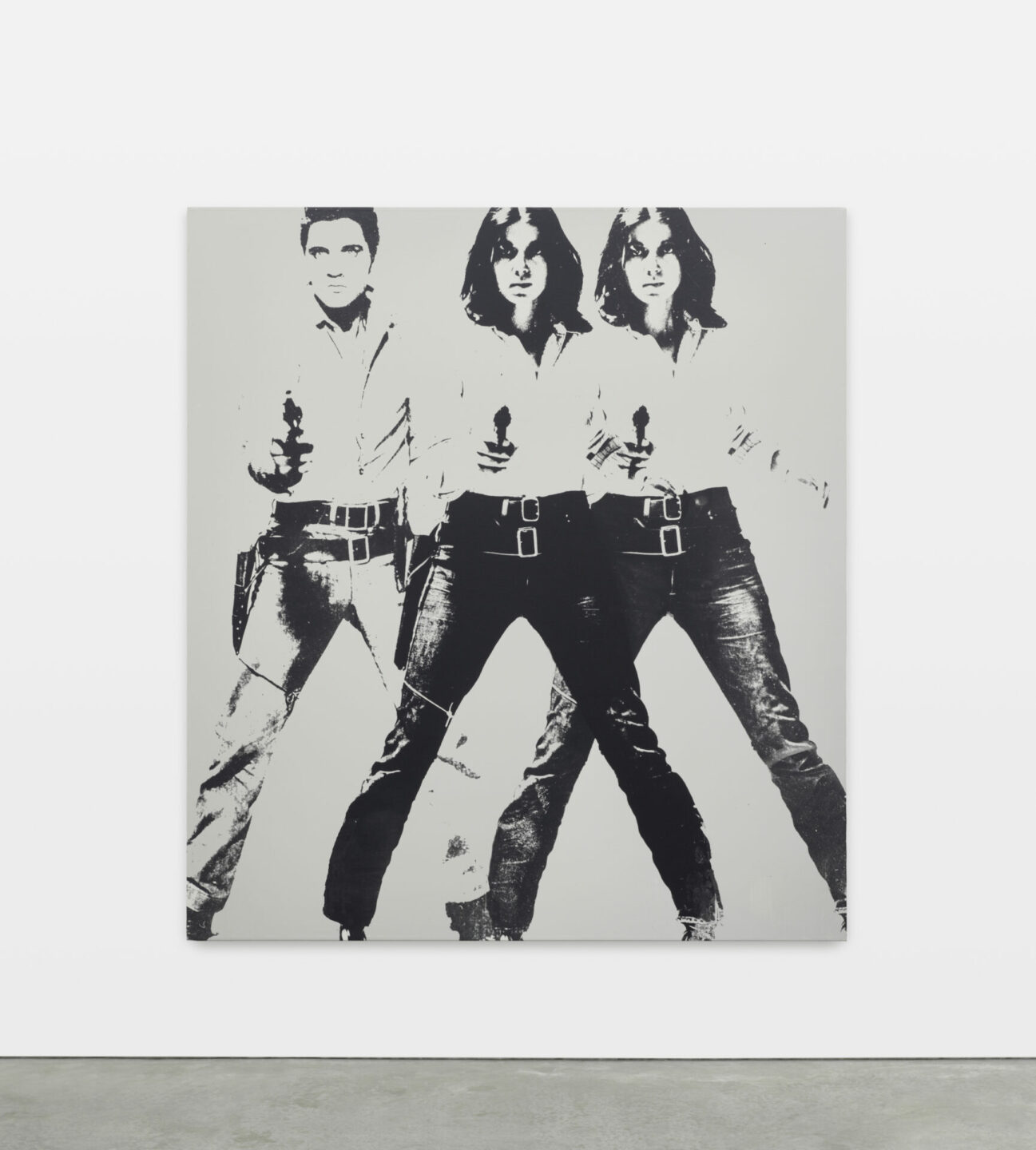

Ulrike Rosenbach. "Art is a Criminal Action III.", 1969/2022. photomontage on photographic canvas. 188 x 170 cm. Courtesy Galerie Gisela Clement.

Social media fame tends to be contextualized as the logical next step to Warhol’s obsession with image. The acclaimed pop artist loved manufacturing the self. Now, decades later, we’re all narcissists publishing selfies to get our own fifteen minutes of fame, but there’s a fundamental difference. While Warhol was otherworldly, the new star aims to be familiar. With live-streaming, vlogging, and the steady trickle of posts, the new star renders themselves an interactive product. Even if they are just as manufactured as before, the democratized nature of social media makes it so that the dynamic can be shifted at a moment’s notice. A random person on the internet can slice a new meme out of you, turning your embarrassing moment into a viral catchphrase. In return, you can throw it back at the masses and hawk overpriced merch. But the dynamic rests on you being willing to open up and let others in — announce engagements and breakups; posting messy hair days and waxing journeys; participating in dance challenges and then smiling when you fall flat on your face.

Warhol’s goal was to copy and paste his artifice forever. He was always in control. When he cameoed in a cheesy TV show, he was performing an amplified idea of himself. It was overexposure but it was never confessional and that’s why his Diaries are so appealing decades after his death. An influencer swaps perfection for accessibility, so trying to emulate Warhol’s canonical, detached definition of “cool” is bound to be clumsy.

An influencer swaps perfection for accessibility, so trying to emulate Warhol’s canonical, detached definition of “cool” is bound to be clumsy.

In Allegra Hobbs’ 2019 essay, “The Journalist As Influencer,” she analyzed how social media has pushed writers to perform a “self-conscious authenticity.” According to Hobbs, in order to accrue readership, writers now need to craft a social media personality that’s self-aware and also act “performatively, romantically messy” online. But art scenes are afforded less flexibility. The Warholian mystique was based on a power dynamic that consumers of celebrity are programmed to crave.

GQ recently published a write-up of Art Basel Miami titled “The Art Week All-Stars.” The header image is a group of vaguely underground models, artists, actors, and writers – all posing in front of boisterously colorful paintings, sporting serious facial expressions. The subheader reads: “We spent a few days with the insiders, outsiders, and party animals at the center of the scene.” But there’s no scene to start with. All these insiders probably spent the better part of the night crafting a glamorous narrative online with varying degrees of success.

An ironic acknowledgment of what’s been lost is a logical next step. In May, Rizzoli will publish a retrospective book by Mark Hunter (aka the Cobrasnake) – a party photographer who documented events throughout the 2000s where alternative icons like Cory Kennedy mingled with mainstream tastemakers like Steve Aoki. The Cobrasnake: Y2Ks Archive is described as a tribute to a time before the “live streaming of culture.” Compiling these moments begs us to buy into a myth.

In the lead-up to his glossy book, the Cobrasnake has been hired to simulate a hazy memory of the Myspace era and photograph the latest crop of downtown parties. His resurgence is an interactive performance, relying on both the artist and spectator to be in on the joke. Put away your phone for a night and let this guy decide what’s hip. Instead of uploading a selfie on your Instagram story, you’ll have to wait for the magazine write-up later this week to see if you made the cut. But this is a power play. You give up control in hopes of getting back. For a night, you relinquish any ability to control the narrative, and maybe if you’re lucky, you succeed on someone else’s terms. Now that anyone can easily crash the Factory, live a fantasy, and have fun at the expense of those who are trying way too hard, there’s an allure to acting as if nothing has changed. It’s not nostalgia, it’s an admission of defeat.