Lena von Goedeke is Making Art in Earth’s Most Extreme Places

Words: Chris Erik Thomas.

An urge to explore the extremes of Earth has always guided Duisburg-born artist Lena von Goedeke. While it has been the most remote reaches of the Pole and Arctic Circle that captivated her and inspired a number of recent works, her entire oeuvre has been united under a focus on form. There’s a tactility to her work, an earthiness that matches the subject matter she casts her eye on. Elements like sand and glass and concrete intermingle with precisely cut pieces of paper, or massive, room-sized air bubbles sit with cables and tubes snaking away.

For over a decade, Goedeke’s love for science and art has been combined to create a range of works that have won her numerous prizes and grants. With exhibitions in Berlin, Paris, Düsseldorf, and many other cities, she has confirmed her status as one of the most interesting young contemporary artists in the region.

Ahead of a showing of one of her works at Art Düsseldorf, we spoke to Goedeke about her work, the importance of art fairs, and how she came to collaborate with Galerie M.

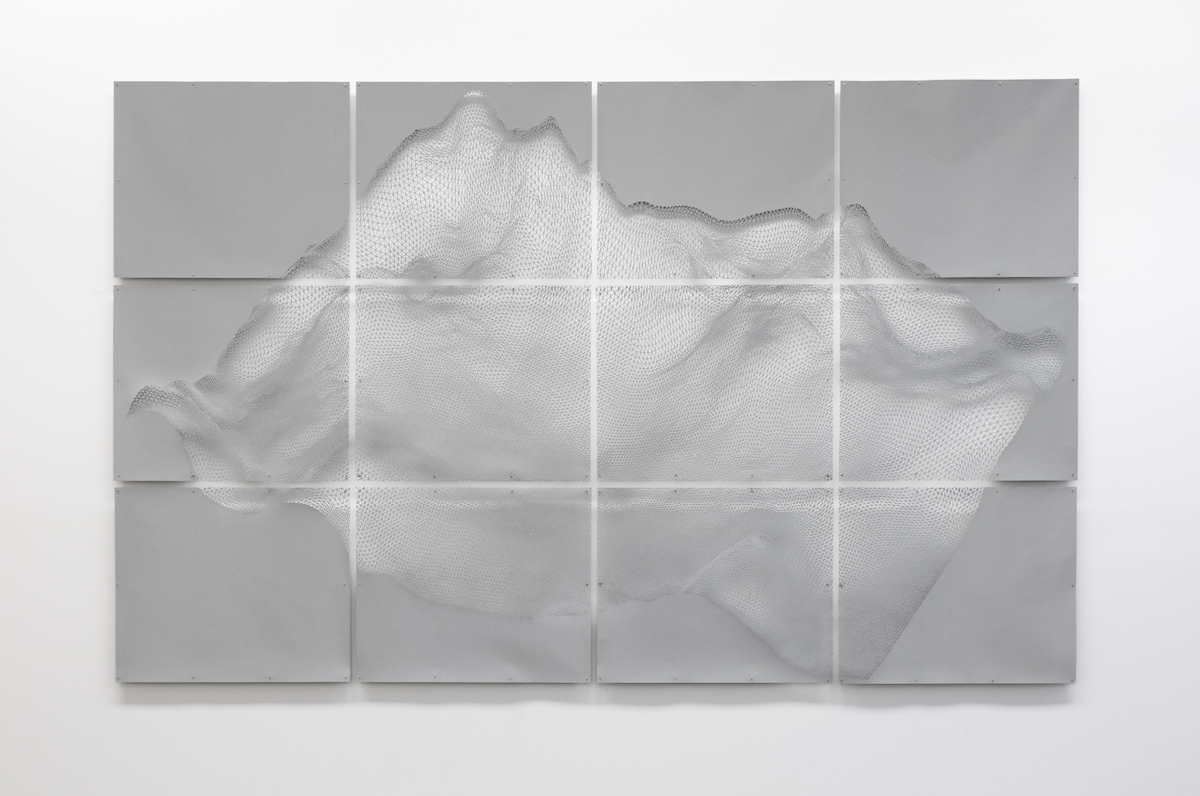

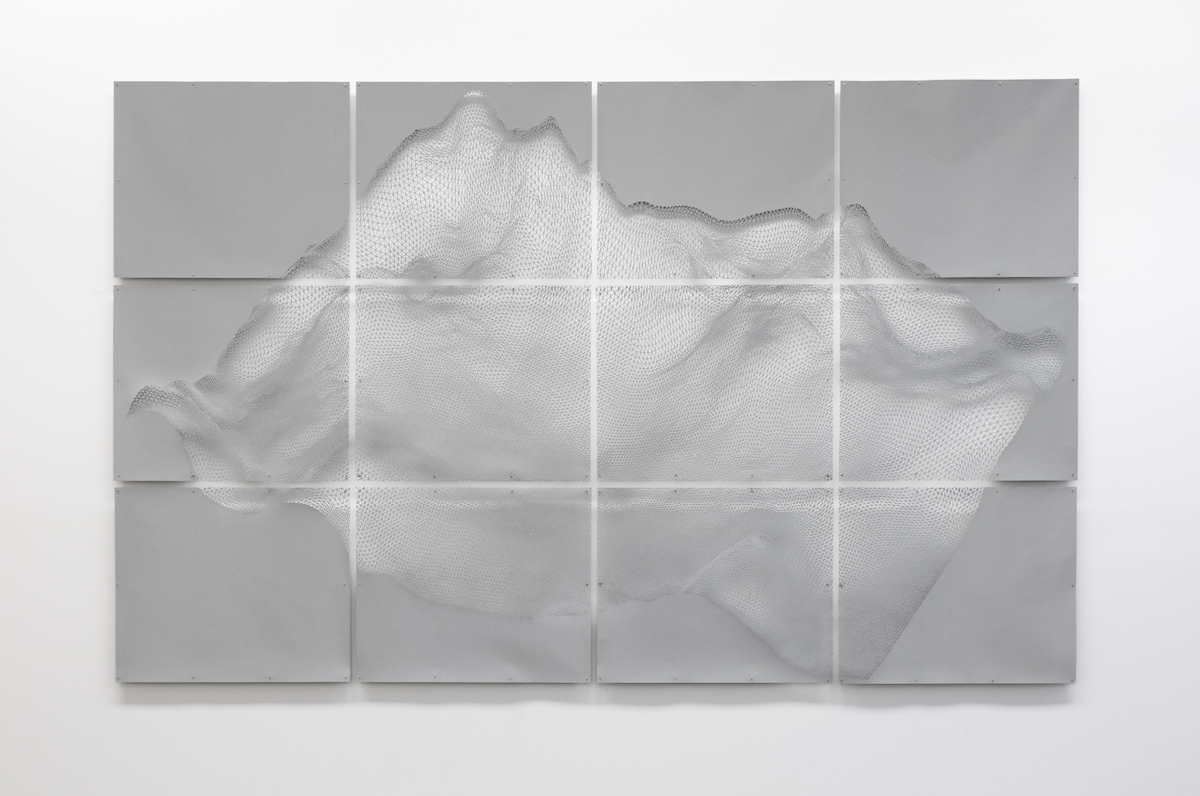

Lena von Goedeke. "Equipment First", Kallmann Museum Ismaning 2021. ©Lena von Goedeke, Courtesy Galerie m, Bochum.

What inspired the works you have on view at Art Düsseldorf?

On my first research trip to the North, I had the opportunity to learn in the science station in Ny-Alesund about the technologies used to measure the surface of our planet and the composition of the thin film in which we exist. All that we know about the space that begins on the outside of our skin, now digitally processed and filtered, fascinated me. Representing the topology of the places we cannot walk ourselves as a wireframe opened up the possibility of taking my ventures in papercutting to a new level.

What message do you want viewers to take away from the art?

LOT VI came about after my first research trip north of the Arctic Circle. In the meantime, I have been able to get to know the Arctic on several expeditions and I keep coming back to the questions that inspired me to create LOT VI: what do we know about the texture of the big rock we live on, in places that we can only see from every perspective with the help of digital tools? How much truth is there in the representation of landscape when the source data consists exclusively of pixels, voxels, or polygons? Especially the extreme places of the planet. The [North and South] poles are known to us only through a few personal experiences and memories of others, or precisely through the flood of digital photography and surveying.

We are so used to the representation of our extended habitat through wireframes that we tend to perceive the depth and perspective of the topography shown rather than the truth of thousands of triangles cut out by hand. I want the viewer of my work to be reminded that we need to trust our eyes if we are not to lose the analog experience of our habitat.

Lena von Goedeke. "The Oneironaut", Galerie m, Bochum 2021. ©Lena von Goedeke, Courtesy Galerie m, Bochum.

I understand art as an indispensable means of understanding the society we have built and the planet we destroyed.

Lena von Goedeke. "Berth & The Perimeter", Dortmunder U 2019. ©Lena von Goedeke, Courtesy Galerie m, Bochum.

How has your artistic practice adapted to the pandemic?

Apart from a few pieces that I have done on the subject, the pandemic has not influenced my work significantly. My reflections on the physical experience of extremes, the limits of our ability to make contact, and the experience of isolation were also important topics in my work before the pandemic. It is a luxury to fill my time extensively with my work and a social necessity to support art and culture. Even more than before, I understand art as an indispensable means of understanding the society we have built and the planet we destroyed.

How important are art fairs for you as an artist? Has that changed at all because of the pandemic?

The very successful Art Düsseldorf 2019 enabled me to get through the first lows of the pandemic and far beyond. If there had been more fairs, a lot would have been possible. Even though many exciting new possibilities and variants [on the art fair format] have developed in the last two years that might have lain in the drawer for too long without the pandemic, it is clear that art must above all be as accessible as possible for as many [people] as possible. No one has a lasting experience in online viewing rooms. You can’t stroll between screens [like you can stroll at art fairs]; scrolling doesn’t make you full.

How did you get involved with Galerie M?

Since the start of our collaboration four years ago, what has developed for me has been an extremely exciting and flexible working relationship. My work is made up of many processes, many different techniques, and I can count on finding an open, enthusiastic, and supportive audience in the gallery.

Galerie M acts as a kind of base camp in Bochum when I’m on the road and can handle thinking from one idea to the next while I stick my nose into the work of academics on the other side of the world.

Lena von Goedeke. "Dunér", 2021. Archival Pigment Print on Baryta. 126 x 86,5 cm (130 x 90 cm framed). ©Lena von Goedeke, Courtesy Galerie m, Bochum.

Your work is very tactile, often using materials like stone, sand, and paper. Where do you draw inspiration for your works and how do you choose the materials to work with?

The foundation of my work consists of the experiences and observations I make in extreme places on this planet. The complex relationship of our physical and social existence to living worlds that we can only access by destroying them, as well as my fascination with scientific technologies and phenomena that go beyond our physical limits, are the framework for my research. In the process, I question materials as to their suitability to resolve my idea as comprehensively as possible within themselves. In this respect, I am open to any material as long as its qualities enable me to convey as precisely as possible the phenomena I am concerned with.

Many of your pieces are site-specific, large-scale installations that force viewers to consider their place within the art. What importance does the viewer have on you and your work?

I act as a mediator between the conditions of the areas I travel to and the viewer. My experiences and memories are the filter through which scientific findings or observations become the work. On the other end, there must be the viewers who then have their own experience and get an impression of how these aspects can be perceived. There must be someone to whom the works can tell something about their origin, somebody willing to learn.

Chris Erik Thomas is the Digital Editor of Art Düsseldorf. They work as a freelance writer and editor in Berlin and focus primarily on culture, art, and media. Their work can also be seen in Highsnobiety, The Face Magazine, and other publications.