Digitization is Key to Creating Sustainable and Equitable Museums

For the first edition of our new essay series at Art Düsseldorf Magazine, we asked a selection of writers to investigate issues related to Sustainability in the Art World. This essay by Aditya Iyer, a London-based journalist, focuses on the need to use digitization as a tool to confront both the climate crisis and the long history of colonialism in art institutions.

Edited by: Chris Erik Thomas, Digital Editor of Art Düsseldorf.

As the arts grapple with climate change and seek innovative ways to lower their carbon footprints, technology has become central to a sustainable future for museums. Lowering the emissions of these institutions may seem fairly low on the priority list while fossil fuel companies continue to belch fetid smog into the sky as they pursue oil profits, but museums are public cultural institutions. The ways they become greener can impart a public narrative as potent as the cultural one represented by the artifacts they house.

At the end of 2022, the director of digital technology at the UK’s National Gallery, Chris Michaels, said that the museum sector is “in a moment of positive momentum” in adapting to the climate crisis. The key to this momentum? Digitization and the disruptions in storytelling and curatorial practices that this process engenders. Michaels was referring to how technology like virtual reality, and programs like the Metaverse, could be used to change how audiences interact with museums.

The possibilities are exciting; The National Museum of African American History & Culture launched digital recreations of its museum floors in November 2021 to boost its outreach. Easily (and cheaply) accessible via smartphones and tablets, the “Searchable Museum” augments the traditional audience experience by recreating key exhibitions and interactive information displays and digitally enhancing a visitor’s experience in some cases. Physical visitors to the museum can see a replica of the Point of Pines Slave Cabin; this digital counterpart is a step ahead and offers access to a 360-degree virtual view inside the cabin. Still, we should not automatically assume that all digitization schemes are a panacea to climate change — or that they automatically constitute a disruption if they do little to change the status quo. Often, they are reminders of the increasingly predatory greed of the sector and represent a new way to make money using questionable technology like NFTs.

NFTs are unlikely to pave the way for a greener museum sector, but the principle of digitization and virtual collections still offer a route toward sustainability.

In the middle of 2021, the British Museum made the controversial move to begin using non-fungible tokens (NFTs) to digitize its collection. The institution, whose digital strategy was shaped in part by Michaels before his departure in 2017, justified its decision by saying that museums had to adapt to “new markets and find new ways of reaching people that we may not reach through traditional channels.”

The questionable financial networks behind NFTs have been extensively written about. One can argue that they devalue the art sector, but the environmental cost of minting them is more germane. The British Museum’s NFT partnership with LaCollection has resulted in its carbon footprint rising by 315 tonnes of CO2 in the first six months of the scheme, according to estimates by the Digiconomist of the carbon footprints of individual Ethereum transactions. The picture gets bleaker using the carbon tracking website Aerial, which estimates that the NFTs have generated an additional 995 tonnes of CO2 emissions since the scheme began. The Ethereum platform has changed its processes from a proof-of-work model to a proof-of-stake model in September 2022, which has led to a significant drop in its energy consumption.

The total carbon footprint may surprise those aware of the Museum’s ambitious new £1 billion “Rosetta Project,” which seeks to modernize the collections and site to make their carbon emissions net zero. But this initial shock should swiftly dwindle considering that its current environmental policy is a forlorn single page that has not been updated since 2007 — plus the Museum’s questionable relationship with British Petroleum.

NFTs are unlikely to pave the way for a greener museum sector, though the technology behind them continues to develop and improve in terms of energy efficiency following criticism of crypto platforms’ high carbon footprints. But the principle of digitization and virtual collections still offer a route toward sustainability. Not just in terms of climate action, but also in radically reimagining the museum anew and divested of its colonial origins.

This philosophy is present in Digital Benin. The virtual repository, launched at the end of 2022, tracks all artifacts looted by marauding British colonial forces from the Benin Kingdom at the end of the 19th Century. Soldiers sent to break the Benin Kingdom by slaughtering its inhabitants compounded their egregious violence by stealing cultural artifacts that eventually made their way to Western museums after being sold to private collectors.

A snapshot of Digital Benin's online catalogue of over 5,200 artifacts. Credit: Digital Benin Catalogue.

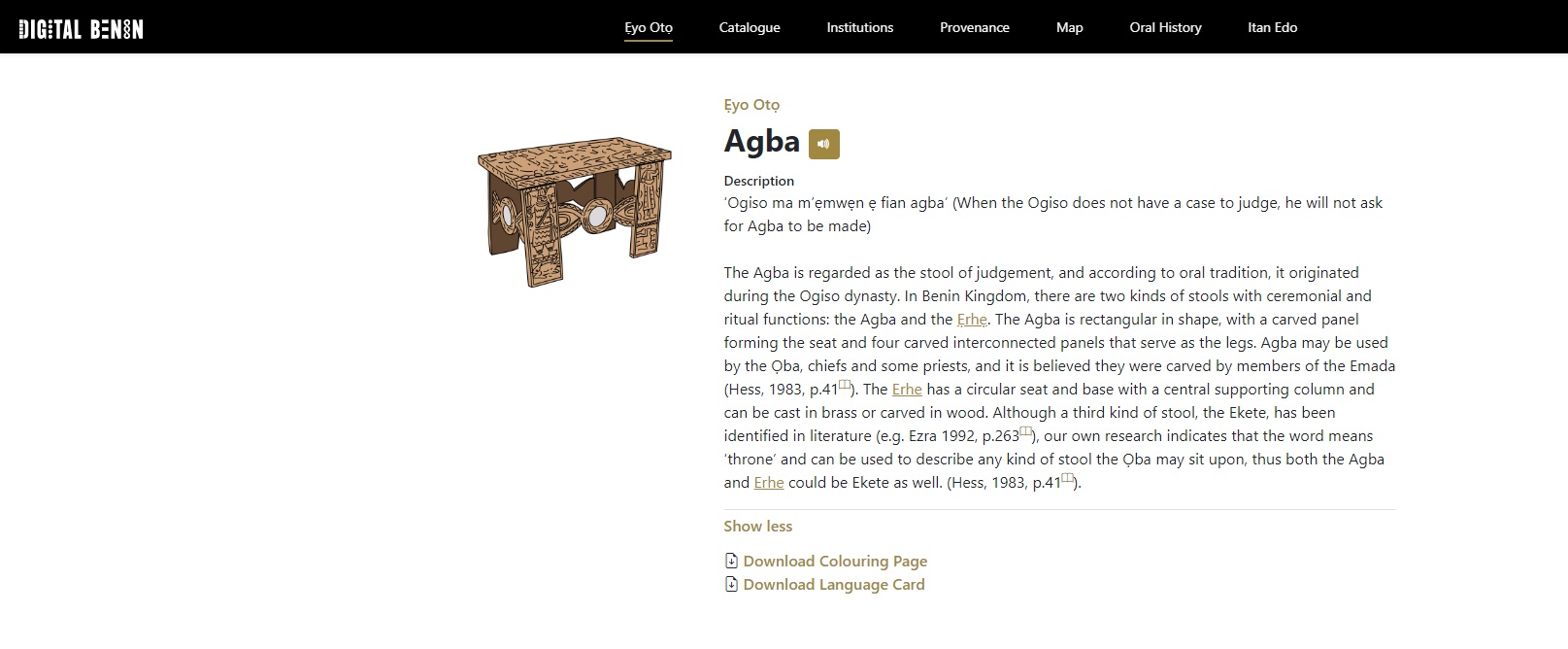

An example image of one of the artifacts cataloged in Digital Benin's online archive. Credit: Digital Benin Catalogue.

Many of these artifacts are now being returned to where they rightfully belong. Berlin’s Humboldt Forum, for example, returned some of the Bronzes within its collection to Nigeria last year. Digital Benin acts as a tally of Western museums that still retain looted Bronzes, and it’s also an indispensable digital archive for scholars and visitors. Rather than the deracinated languages used by Western museums, Digital Benin displays the historical objects with their correct Edo designations and cultural contexts — skewering the idea that the expertise of the culture that produced these artifacts is somehow inferior to that of their Western counterparts.

As Aime Cesaire wrote in his seminal 1950 work Discourse on Colonialism, the hideous butcheries of imperialism were “based on contempt for the native and justified by the contempt.” The creation and evolution of the modern museum has been intrinsically tied to this legitimation by serving as receptacles for colonial power. Loot was displayed as “artifacts”; their violent translocation was as much a sign of Western martial prowess as the clinical placards accompanying their exhibitions of a purported racially superior intellect.

Museums housed more than just the spoils of colonial conquests; among other objects, some even included human remains. It was a practice that echoes the legacy of zoos using “living exhibitions” of those deemed racially inferior to present specific narratives to the public. Following the Second World War, this fell out of favor as the violent consequences of clearly defining groups of people as being “lesser” came home to Europe for the first time since colonization began. But mild discomfort took time to boil over to outright condemnation. The last human zoo in Europe shuttered in 1958, nearly a decade after The Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognized the “equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family.”

There is little use for a net zero museum if it still serves the purposes fashioned for it by a crueler time.

To be truly sustainable, art institutions must do more than simply improve ventilation and find energy-efficient storage options to house looted artifacts, as per the Bizot Green Protocol. Digitizing collections must go hand-in-hand with returning colonial loot to make museums culturally sustainable for the 21st century. As the founder of the African Digital Heritage project and one of the consultants responsible for Digital Benin, Chao Tayiana Maina, has said: digitization should be viewed “as a curatorial [and] cultural process […] looking at the society, looking at the ethics and community to allow us to ask questions as oppose to just data.” The latter is impersonal and faceless, and can potentially lead to a different kind of exploitation by creating, in a sense, virtual “loot.” Calls to create digital representations of every artifact seem innocuous on the surface, but what if said objects were sacred and fundamental to the spiritual practices of a local community, one whose assent was most likely not sought before creating a 3D model for an online audience to view?

One of the most valuable aspects of the Digital Benin project is that it collects Edo experts’ knowledge about each artifact’s cultural context and functions. By breaking the fundamentally unequal power structures that traditional museum curatorial narratives represent, this disruption informs new discourse surrounding artifacts, the cultures they were taken from, and their roles and values. As Maina has also stated, technology breaks down the traditional gatekeeping “silos and systems of power” by acting as a tool for new narratives to articulate themselves and as a platform to access new audiences.

Attempts to make the art sector sustainable must focus on its own messy history as much as its carbon footprints. There is little use for a net zero museum if it still serves the purposes fashioned for it by a crueler time. Museums have the opportunity to do more than simply lower the carbon footprint of exhibitions that serve the same exploitative narratives of the past. By recognizing how they harmed the environment in the past, institutions have begun to take steps toward mitigating their ecological impact in the future. However, these tools should not be used to focus solely on climate change, but can and must be used to do the same with regard to human dignity. Only then can art institutions build a truly sustainable and equal future for all.

Aditya Iyer is a journalist and writer based in London who writes about the intersection between culture, identity, and public memory, with a focus on how colonial histories continue to shape the contemporary world.