The application process for 2025 is starting on August 28, 2024 // Next Art Düsseldorf: April 11-13, 2025

The application process for Art Düsseldorf 2025 starts on August 28, 2024. All information will then be found here on the website. If you have any questions in advance, please get in touch with our gallery manager.

REVIEW 2024: OUR MOST READ ARTICLES

Save the Date

April

11-13

2025

11-13

2025

Save the Date

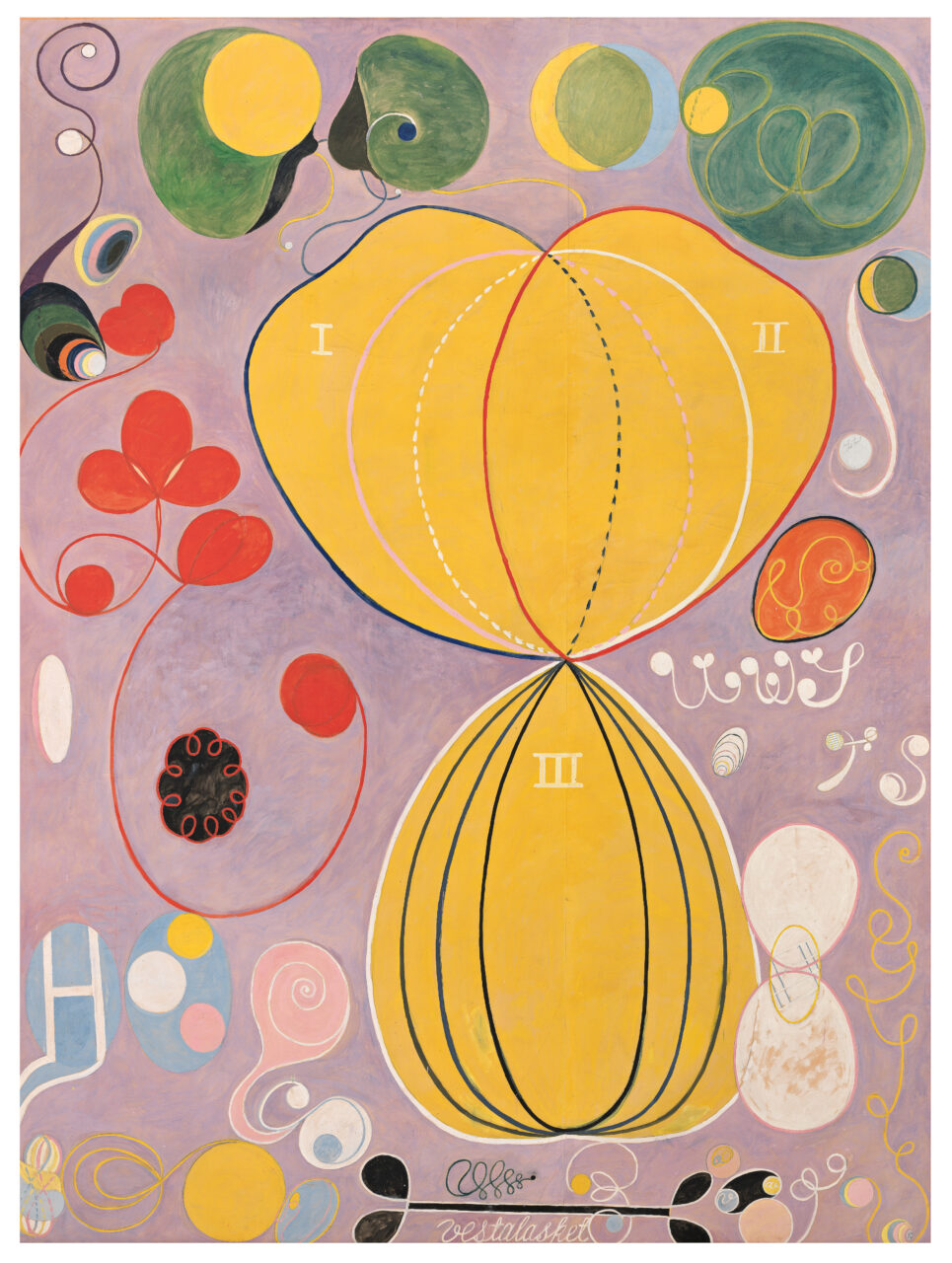

Impressions of Art Düsseldorf 2024